In the wake of the economic downturn provoked by the COVID-19 pandemic, criticism of the China-led international development efforts in Africa has accelerated, prompting a review of the conditions under which China provides aid to the development of African infrastructure and economies. The debate over whether Chinese loans are a fair deal for African states and whether the securities associated with such agreements are in violation of the countries’ fundamental interests has intensified, with critics claiming China’s terms hurt national sovereignty.

Given the sensitivity of the topic, it is not surprising that the conversation has become heavily politicized in several African nations. Not all of the arguments are based on facts, though. In particular, healthy debate on the merits of Chinese-offered contracts should avoid confusion due to a misunderstanding of the legal terms in these agreements.

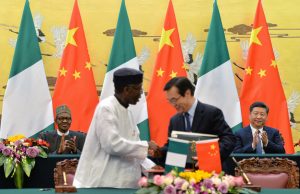

Last week an example of this confusion arose in Nigeria. A clause in a commercial loan agreement signed on September 5, 2018 between the Federal Ministry of Finance and the Export-Import Bank of China for the Nigeria National Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Infrastructure Backbone Phase II Project caught public attention when it was examined by Nigerian lawmakers. The clause states:

[T]he Borrower [i.e., the state of Nigeria] hereby irrevocably waives any immunity on the grounds of sovereign or otherwise for itself and its property in connection with any arbitration proceeding pursuant to Article 8(5), thereof with the enforcement of any arbitral award pursuant thereto, except for the military assets and diplomatic assets.

Researchers have pointed out that clauses like this appear to be standard in Chinese loan contracts.

Is there any merit to the claim that Nigeria is “conceding sovereignty to China” through this clause? This article seeks to provide legal elements to help the analyze the case, based on the information made public in the press.

Any assessment of the legal impact of a contractual clause requires a thorough reading of its precise terms. Legal language matters a great deal, and professional lawyers dedicate substantial effort to the careful drafting of contract provisions that reflect the exact balance and intention of the parties. Journalistic shortcuts can quintessentially modify the meaning of a stipulation and lead to a wrongful interpretation of the legal effect of a contract.

In this instance, it is important to note that the exact contractual terms are that the Nigerian side agrees “to irrevocably waive immunity on the grounds of sovereign or otherwise” (emphasis added), not “waive sovereignty.”

What Is Immunity?

Immunity is a legal privilege enjoyed by independent states as well as international organizations. There are two types of immunity under international public law:

- Immunity from jurisdiction, by which a state cannot be sued before the courts of another sovereign state without its consent; note that by extension, the immunity will also encompass arbitral tribunals. Shortly put, in contrast to private agents such as natural persons and private companies, which are compelled to appear before a judge to answer a claim, states can refuse to participate in a litigation launched against them before the foreign court of another state or an arbitrator.

- Immunity from execution, protecting stately assets from seizure by the law enforcement agencies of another state.

State immunity is considered to derive from the customary practice as well as the “general principles of law recognized by civilized nations,” both being sources of international law under the Charter of the United Nations.

The founding principle for immunity lies in the Latin adage “par in parem non habet imperium” (as translated by Oxford Reference, “equals do not have authority over one another”), meaning that no state can impose its justice over another independent state. State immunity is therefore grounded in the inherent equality of sovereign states.

Therefore the condition for enjoying the privilege of immunity — and using it to avoid enforcement of a binding arbitration award or other legal judgment — is to be recognized as a sovereign state (as is the case with Nigeria). All sovereign states have immunity as a sovereign attribute, simply by being sovereign states. This explains the reference in the clause to a privilege “on the ground of sovereign.”

Can Immunity Be Waived, and Why Did Nigeria Waive It in This Instance?

Sovereign states enjoying the privilege of immunity can elect to waive it, much like a private individual or any other legal subject can choose to renounce a right.

The decision to waive a right is usually based on an appreciation of the advantages that can be received in exchange. For example, every natural person has a right to receive adequate pay for their work, based on the prohibition of slavery under international law. The right arises from their capacity as a human being (animals do not enjoy similar protection and can be legally put to work without compensation). Nevertheless, a person is entitled to perform work without remuneration, if it be their free choice. The reasons for which a person may elect to do so are many — development of a business network, gracious assistance, etc. — and depend on the scenario at hand.

In the context of an international contract, the parties will inevitably need to agree on the designation of a third party that will review any dispute arising in the course of performing their contractual obligations. Such an independent auditor can be either a foreign court or, more commonly, an arbitral tribunal. If a party (being a sovereign state) could, on the basis of its privilege of immunity, escape the jurisdiction of the chosen tribunal (immunity of jurisdiction) or refuse to implement its decision (immunity of execution), then there would be little efficiency attached to the jurisdiction mechanism and correlatively, little incentive for anyone to enter into the contract in the first place. For this reason, it is common practice when a state is party to a contract (either directly or acting through one of its agencies) to require a waiver of immunity in order to ensure that the dispute resolution mechanism will be effective if and when required.

As with the analogy on unpaid work, the key concept is that the renunciation is freely consented after (one assumes) careful review of the consideration offered for this waiver.

Going back to the Nigerian loan, the consent by the Nigerian state to appear before the chosen arbitration tribunal, should a dispute arise, by waiving its immunity of jurisdiction appears to have been the condition for the Chinese party to enter into the loan agreement. Unless there are other clauses in the agreement that were not publicly commented on, and contradict this interpretation, the position on the part of the Nigerian state does not appear to be unreasonable and is in line with standard practice in international contracts with states.

What Is the Effect of Waiving Immunity?

Waivers like this are limited to the legal instrument under which they are given. Therefore, the sovereign immunity privilege was only waived here for the implementation of the loan agreement with Exim Bank of China of 2018. The state of Nigeria retains its privilege for any other circumstance; even in the context of the agreement, only the contractual counterpart Exim Bank (excluding another third party) can claim to benefit from the waiver. For this reason, Nigeria’s inherent sovereignty remains untouched by the signature of such clause.

Therefore, it cannot be inferred from the above terms of the contract alone that Nigeria has renounced its sovereignty in favor of China, no more than a person loses their humanity by choosing to perform free work.

Unlike a national court, an arbitration tribunal has no inherent power of jurisdiction, and its authority arises from the parties’ consent to appear before them. A party can never be brought before an arbitrator against its consent. Here again, Nigeria’s consent to the dispute resolution clause lies in the perceived economic reward of granting such consent: persuading the Chinese party to enter into the loan agreement.

What About the Waiver Concerning Nigeria’s Assets?

Again, it’s a question of consent and scope. As a sovereign state, the assets of Nigeria are protected by immunity from execution, which means that they cannot be seized by another party. That said, any lender granting a loan will require that some security be attached to guarantee the lender against the default of the borrower. In the case of investment agreements, that security may take the form of a guarantee letter signed by the state (usually, the Ministry of Finance in which case it is known as a sovereign guarantee because it emanates from a state agency), or a security over a particular asset (which can be a plot of land, for example). If the borrowing state could object to the seizure of such collateral based on sovereign immunity of its assets, then there would be little incentive for the lender to grant any loan. As with the jurisdiction, the waiver is limited to the context of this particular agreement.

Sovereignty means the legal ability for a modern nation-state, as the sole ruler of a territory and population, to make its own rules and implement its decisions without reference to a superior power. It also entails the right to delegate or, as in this instance, renounce some of its attributes. While the exercise of sovereign rights by a state may be influenced by economic pressure, this sensitive political concept can also be misreported on. Analysts reviewing the conditions under which China, as a foreign investor, enters into investment contracts with African nations should exercise caution to correctly separate unfair or inopportune contractual terms from actual sovereignty grabs.

Laure Deron, Avocat au Barreau de Paris, has many years of experience in private practice for leading law firms based in Paris, France and Beijing, China. Currently Deron is a lecturer in company law and Sino-European economic relations at the University of Paris.