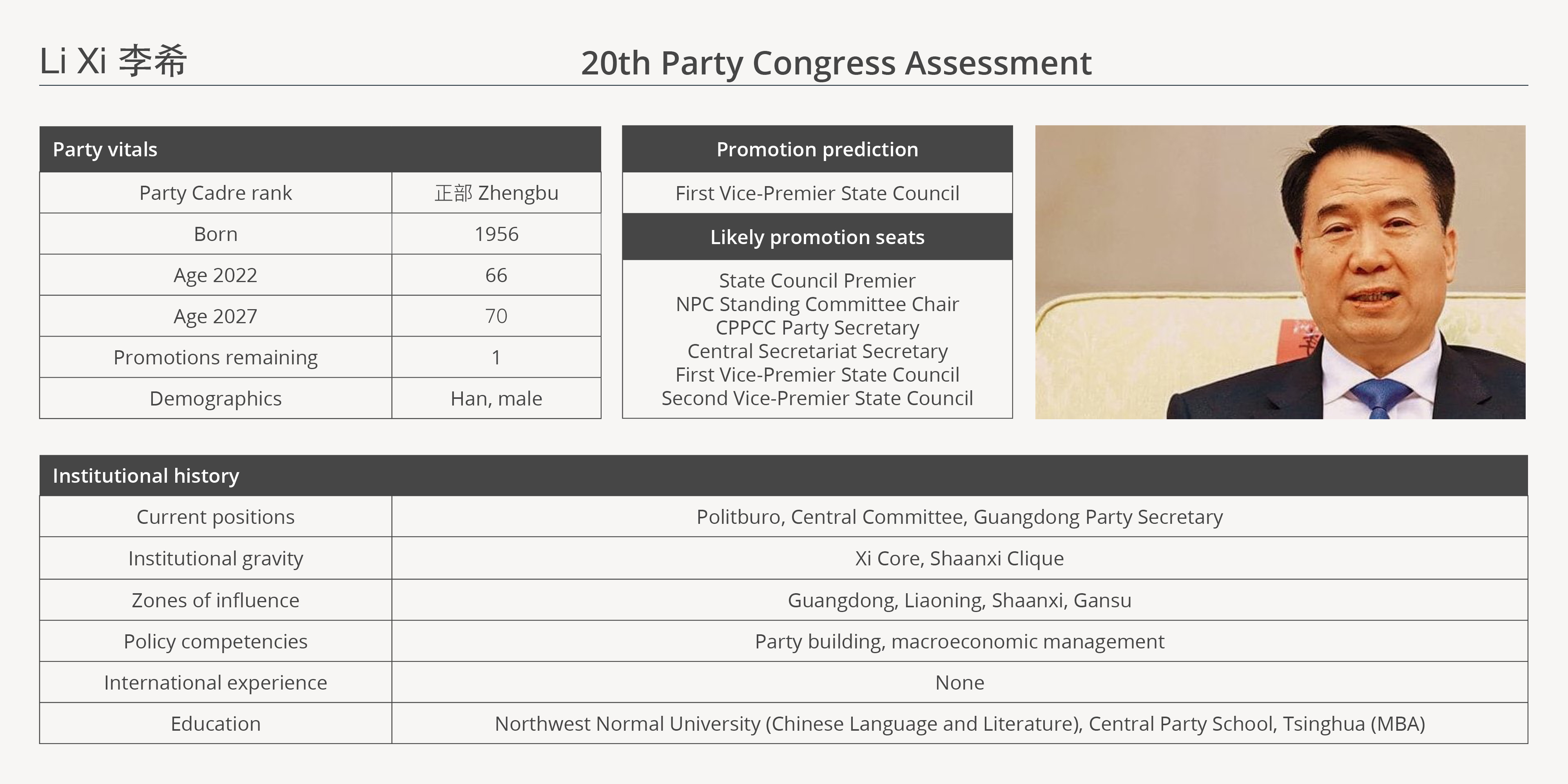

As head of the largest economy in China, Guangdong Party Secretary Li Xi is at the forefront of technoindustrial policy, trade policy, economic reform, and regional integration. Li Xi has one more promotion left in his career; he will almost certainly join the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) at the 20th Party Congress in 2022. Li has been a loyal stalwart of the Xi Jinping project, and falls firmly into the core camp. His five-year stint as Guangdong party secretary is probably the safest, and most powerful, seat outside the PBSC, signaling the trust placed in him. His position in the 20th Party Congress Politburo Standing Committee is the only real variable now. Li Xi is likely to sit in either the first vice premier of the State Council or Central Secretariat secretary seat, depending on whether Wang Huning stays or moves into a new role within the Standing Committee.

Li’s early life and party career were in Gansu, working for his hometown country party offices from age 20, even before his bachelor’s study. After graduation he went straight to the Gansu provincial Propaganda Department, and then on to the General Office briefly before various roles in the provincial Organization Department from 1986 to 1995. After a year as party secretary at the county level in Xigu, Li went up to the prefectural level in Lanzhou, again in the Organization Department. He then moved sideways to a higher position in a lower prefecture, serving four years at Zhangye prefecture, while also completing the Central Party School mid-career training. A final promotion to Gansu provincial level allowed him to move up to Shaanxi province.

Li’s rapid and competent rise through Gansu meant that he then qualified for the “political grand tour,” the institutional prerequisite for eventually ascending to national politics. This is a crucial stage in a China politician’s career, because the party cadre rank does not change much from here until either national leadership or retiring into obscurity. A strange quirk of China’s political system is that there are no truly national level positions — for such an ostensibly centralized Leninist political structure, China operates far more like a federal system. Once a cadre has risen to provincial minister level, the political landscape consists of a series of tours of duty to prove loyalty, build factional relationships, gain cross-country experience, and manage increasingly larger populations and economies. For Li, his political grand tour was through Shaanxi, Shanghai, Liaoning, and finally Guangdong over a period of 18 years.

Li’s first nine years in Shaanxi cemented his position in the regional political tournament system. He sat on the Provincial Party Committee and was party secretary of Yan’an prefecture, a significant site in CCP history. Three years in Shanghai followed, back to his preferred Organization Department role while also with a hand in cadre training at the provincial Party School. The timing of his appointment as party secretary of Liaoning in 2014, briefly as acting governor and then more permanently as party secretary, was significant given Xi Jinping’s desire to secure the province that had been a power base of rival Bo Xilai during his ascendency through Dalian. For the 19th Party Congress, Li has been party secretary of Guangdong province, sitting on the Politburo as one of the six provincial boss seats.

Li is thus part of Xi Jinping’s core political faction, cemented in his time in Shanghai and an important member of the Shaanxi Clique. As Guangdong party secretary, he was the most powerful non-Standing Committee politician in China for the past five years. At the central level, Li was an alternate member in the 2007-2012 17th and 2012-2017 18th Party Congresses, and a full member of the 19th Party Congress since 2017.

Li’s core status is predictable given his party roles throughout his career. The Organization Department, Propaganda Department, and General Office are all core CCP organs, replicated at every level of the party hierarchy, with the central level organs being represented on the Politburo. This would normally put Li in line for a core position in the Standing Committee, as the Central Secretariat or the National People’s Congress Standing Committee chair. However Li’s most important position has been as party secretary of Guangdong province, running a huge macroeconomic project, making him a more practical, policy-oriented politician, and part of a group of core acolytes currently in the provincial party boss seats. To have worked through the central Organization Department, Propaganda Department, or General Office he could have been in the Politburo and continued into the Standing Committee in a core party position. But as he has taken a more practical approach, particularly since his tours of duty in Shanghai, Liaoning, and Guangdong, Li is now more in line for one of the State Council positions, especially given the indications are that Xi would continue to weaken the independence of the state in those positions, bringing them closer to party policy priorities.

Li’s core status is predictable given his party roles throughout his career. The Organization Department, Propaganda Department, and General Office are all core CCP organs, replicated at every level of the party hierarchy, with the central level organs being represented on the Politburo. This would normally put Li in line for a core position in the Standing Committee, as the Central Secretariat or the National People’s Congress Standing Committee chair. However Li’s most important position has been as party secretary of Guangdong province, running a huge macroeconomic project, making him a more practical, policy-oriented politician, and part of a group of core acolytes currently in the provincial party boss seats. To have worked through the central Organization Department, Propaganda Department, or General Office he could have been in the Politburo and continued into the Standing Committee in a core party position. But as he has taken a more practical approach, particularly since his tours of duty in Shanghai, Liaoning, and Guangdong, Li is now more in line for one of the State Council positions, especially given the indications are that Xi would continue to weaken the independence of the state in those positions, bringing them closer to party policy priorities.

Li’s policy trajectory in Guangdong in 2017 points to his likely contribution to 2022-2027 elite leadership, much like a United States senator’s voting record might be examined to extrapolate possible future institutionalized behavior. Li is the highest domestic political authority responsible for development of the Greater Bay Area, the latest incarnation of the decades-old economic integration plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao area, which has taken on extreme politicized force in 2020. Li has also led implementation of industrial integration and upgrading across the province’s industrial base such as under the “1+1+9” macroeconomic governance model for Guangdong and its component subprovincial public administrative units. The first “1” is strengthening CCP leadership; the second “1” is deepening reform; and the “9” refers to a series of macroeconomic and long-term political objectives for the province. Li has also been tasked with the local practical political implementation of “Spiritual Civilization,” the highest order ideological framework for the Xi administration. That the most marketized and international-facing provincial economy in China has so successfully restrengthened party-political control over market institutions under Li’s tenure is telling.

Li’s major policy weakness is a lack of formal international qualifications. Many current high-ranking cadres have either studied or worked abroad, a trend that will only become more ubiquitous as younger candidates move into the elite leadership cohort of the 2022-2032 period. However, Li has been increasingly exposed to practical foreign policy, for example meeting India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar in New Delhi in 2019. Li has also overseen major foreign policy practice in heading the most international-facing province in China’s state-market economy. Under Li’s tenure, Guangdong has become a principal node in the Maritime Silk Road project, coordinating the Pacific Islands arm of the Belt and Road. Li has also coordinated China’s institutional takeover of Hong Kong as the highest level regional politician responsible for the 2020 changes. While Li will not be China’s foreign policy face to world, expect him to have a strong hand in China’s geoeconomic policy and CCP foreign policy.

Li Xi will almost certainly ascend to Politburo Standing Committee in 2022 as long as Xi Jinping or at least a Xi-dominated CCP remain in power. As an absolute Xi stalwart, Li will have to hold together and implement a series of carefully orchestrated political and economic policy narratives. Whatever Li’s position in the 2022 Politburo, expect his portfolio to be tasked with tough-to-implement policies that further politicize market institutions.