While “empire” is a word best shunned in contemporary political discourse, imperial legacies live on — in Asia and elsewhere — shaping geopolitics and raising the specter of conflict. China under President Xi Jinping seeks to shape itself both as a modern one-party state, but also tries to draw its legitimacy, at home and abroad, from thousands of years of imperial legacy. Vladimir Putin’s Russia not only has positioned itself as a successor to the Soviet Union, but Kremlin supporters – through its cultivation of the Russian Orthodox Church – normatively equate Moscow and Rome, the seat of the Catholic Church. India under the Bharatiya Janata Party and Prime Minister Narendra Modi speaks of itself as a “civilizational state” that predates Islamic invaders and European colonization – and is eager to restore lost glory. The United States’ informal empire leads to periodic calls for isolationism and manifests itself in unexpected ways in the country’s domestic politics.

In a new book, Samir Puri, a former official in the British Foreign Office and now, a senior fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, Singapore, looks at how imperial legacies shape geopolitics, often to pernicious effects. Drawing on a big-picture view of history combined with political analysis of contemporary events, Puri’s “The Great Imperial Hangover: How Empires Have Shaped the World” presents a comprehensive picture of a post-imperial world. He recently spoke with The Diplomat’s Security & Defense Editor Abhijnan Rej over email about his book and more.

You write, stating the central thesis of your book, “twenty-first century world order is a story of many post-imperial legacies. When these legacies collide, misunderstanding, friction, schism or even war can result.” To what extent are these “post-imperial legacies” related to contemporary narratives of lost glory? Are the perennially aggrieved, as one could describe Vladimir Putin’s Russia, for example, a threat to international security?

The writing process [for the book] began a year after I returned from the Ukraine war, where I had worked in a multinational mission that was monitoring a failing ceasefire. The reverberations of Russia’s imperial past were on my mind – there was a clear parallel between imperial conquest and the annexation of Crimea in 2014. But there was a less obvious psychological dimension; in how the ghosts of empires stalk the consciousness of modern nations. During my monitoring duties I met members of both the Ukrainian and Russian armed forces (the latter had an official presence in the war zone as part of its own monitoring mission, called the “JCCC” [Joint Center for Control and Coordination]). In relation to the Russian armed forces, the pride of Mother Russia inspired them; whether incarnated in the USSR or in imperial Russia, their grandfathers and great-grandfathers had fought to defend and expand their realm. Russia’s present regime harnesses this imperial past in its ideology.

I returned from Ukraine and switched career to academia and writing. Then, closer to home, came the U.K.’s Brexit referendum in June 2016 alongside its own set of issues. The influence of British imperial legacies on the referendum’s outcome was small but subtle. You could see it in how the ideals of Brexit were impelled by conceptions of British greatness. Specifically, Brexiteer politicians, journalists, and businessman thought that Britain took a wrong turn in 1973 by joining the European Economic Community, seemingly at the expense of Commonwealth ties across its old imperial realm. Some Brexiteers were forthright about the significance of the Anglosphere, for instance. And their concept of national greatness was influenced by allusions to Britain as a “great trading nation” – a notion that makes no sense if discounting the five centuries during which England and then Britain was an imperial power. In the instance of Brexit, imperial legacies acted as an unconscious reference point.

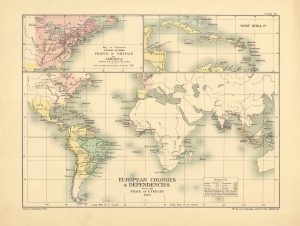

In the previous century the whole world experienced the end of formal empires. Hence my book embarks on a world tour, looking at the world’s variegated imperial legacies and their lingering influences on a host of modern issues. Empires tend to deposit a mix of practical and psychological legacies as they expire, and many such legacies are still influencing our world.

To what extent does China under Xi Jinping seek to reconcile its post-1949 status as a modern one-party state with its imperial legacy and civilizational claims? More fundamentally, to what extent is its official Communist ideology consistent with Chinese imperial traditions?

Trying to understand the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) only in terms of its own 100-year history strikes me as a rather narrow perspective. When writing the chapter on China, I delved far further back in time than the founding of the CCP in 1921 and the revolution in 1949. The eras of the Chinese civil war, of Mao Zedong’s and of Deng Xiaoping’s rulerships still exert immense proximate influences on China. But China’s older and longer imperial past diffuses a different set of influences, some of which provide a different source of inspiration for China’s ascent.

Take the matter of China’s modern borders. It is remarkable how similar these borders are to that of the Qing Empire (1644-1912). The CCP, from Mao to Xi, says that its efforts ended China’s “century of humiliation” at the hands of the Japanese and European imperial powers. The CCP did this in part by transforming China’s imperial realm into a state. Xinjiang, Tibet, and Mongolia were subject to different kinds of occupations by the Qing dynasty, which also brought its home province of Manchuria more firmly into the Chinese fold. Consider also the precedent set by the intra-empire relations of the Qing and Russia’s tsars. Although there were tussles over the spoils of the old khanates along their border, a coexistence was managed with Catherine the Great, who coincidentally died in 1796, the same time that the 61-year reign of the celebrated Qianlong Emperor ended.

What the CCP achieved – if we take the long view of history – was to bring to 20th/21st century standards to the vast landmass and polity that occupies the space of the old Chinese empire. Moreover, such a long history of central imperial rule has established its own antecedents for modern one-party rule. This year, as the CCP marks the centenary of its founding, and with China physiologically emboldened by its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are plenty of breaking events to draw our attention. But we should still also pay attention to the older imperial influences behind China’s self-identity.

The Narendra Modi government in India repeatedly describes itself as a “civilizational state.” What is the precise link between such claims, imperial ambitions as well as legacies, even as — as you argue in your book — India will have to chart its course in a post-imperial world and figure out where its place is in it?

The chapter on India was absorbing to write, given my ancestry. As anyone of Indian origin will tell you, the collective identity of Bharata matters only as much as one’s more specific regional origins. Hence, any notion of an “Indian civilization” must contend with what [Indian politician and former U.N. diplomat] Shashi Tharoor once nicknamed the “thali dish” of Indian society, with different communities existing in both glorious individuality and splendid togetherness.

This is why Tharoor and others dislike the Modi government’s majoritarian policies. Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party have said that Hinduism is India’s civilizational locus, based on Hindutva ideas. To my reading, the 1923 book on Hindutva by V. D. Savarkar has a fascinating subtext: Its majoritarian stance can help Hindus to reject the humiliation of having been conquered by successive Muslim, Portuguese, and British empires. Think about the power of claiming a civilization continuity from a time that predates the occupations by Muslims and Europeans. Savakar waxes lyrical about Shivaji’s Maratha resistance to the Mughal Empire, for instance. Also bear in mind Savakar’s previous book entitled “The Indian War of Independence, 1857,” about the failed anti-British sepoy mutiny.

Many people see modern populism as being driven by current trends alone, but I am also interested in how populism makes emotional appeals to certain interpretations of history. Despite the controversies that Hindutva has been mired in regarding its claims around the specific origins of the Aryan people, it has helped Modi to forge a psychological bond with many Indians, in part because how it frames their sense of religious and historical identity.

This can be seen when Modi cast the foundation stone for the Lord Rama temple in Ayodhya, which is being built at the site of the former Babri Masjid (the 16th century mosque that was named after Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire). Consider also Modi’s plan to replace the old British-era parliament building that is currently used as the Lok Sabha with a grand new construction, in time for the 75th anniversary of the end of the Raj.

With the January 6 storming of the U.S. Capitol in mind: To what extent has American “imperialism” been linked with American exceptionalism? What role does credibility and the ability to persuade other polities play in sustaining empires – or pushing back against post-imperial legacies?

We are still grasping the consequences of the events of January 6. The United States is facing a difficult reckoning with its self-conception as an exceptional nation. Recent events show that a portion of its populace are just as susceptible to demagoguery and radicalization as anywhere else on earth. The incoming Biden administration will have its work cut out for it in assuaging tensions over racial and cultural issues, as well as making a renewed claim for informal empire abroad.

On the domestic front, it has been said that some of the scars of the U.S. Civil War never truly healed despite the passage of 156 years. Just look at the image of the Confederate flag being paraded through the Capitol Building by the January 6 insurrectionists. It seems that with tension over racial issues heightening to an extent not seen for a generation, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests have produced a strong counterreaction.

This is where America’s imperial inheritances come in. Slavery was an imperial export, after all, with the European empires forcefully moving African slaves to the New World to work on the plantations. The New York Times recently tried to push its “1619 project,” situating the year and the arrival of the slave ships at the English colony of Virginia more centrally in America’s historical narrative. The 1619 Project has caused its own backlash, just like BLM.

The U.S. was founded as a forward-looking nation but in an age of empires. Indeed, the U.S. expanded in the 1800s to the Pacific coast and to its southwestern land border through white settler conquest. Recall how Donald Trump whipped up a storm amongst his supporters about the Mexico-USA border – this border exists as an outcome of past territorial wars and annexations, practices that were entirely normal in an age of empires, but that linger in their consequences as hangovers from a bygone age.

In a 2014 essay, Robert Kaplan wrote: “In geopolitics, the past never dies and there is no modern world.” Is this statement in sync with the central arguments of your book?

Yes, and imagine my delight when Robert D. Kaplan agreed to endorse my book. As for many of us who have combined adventurous travel and geopolitical writing, Kaplan is well regarded. My personal favorite quote comes from his “Monsoon” book in which he describes “a non-Western world of astonishing interdependence and yet fiercely guarded sovereignty.” I hope “The Great Imperial Hangover” makes its own humble contribution in examining this paradox.