Few people have experienced the ups and down of China-U.S. relations as closely, and for as long, as Dr. Chi Wang. Wang came to the United States from China in 1949, just before the People’s Republic of China was founded. He eventually became the head of the U.S. Library of Congress’ Chinese and Korean section, and spearheaded people-to-people educational exchanges during the initial opening of the 1970s. In 1995, Wang co-founded the U.S.-China Policy Foundation, where he still serves as president (disclosure: I previously worked for Wang and the USCPF).

Wang outlined his experiences as a Chinese American, from 1949 to the present, in his memoir, “A Compelling Journey From Peking to Washington.” In this interview, he talks about his past, anti-Asian racism in the United States, and the historical context for today’s tensions in China-U.S. relations.

You came to America in 1949, with both countries fresh off the experience of the U.S.-China alliance in World War II. Then came the Korean War, a lengthy period of Cold War antagonism, a high-profile normalization process in the 1970s, and today a return to deep tensions. How have the up-and-downs of U.S.-China relations impacted perceptions of Chinese Americans over the past 70+ years?

When I first left China, everything I knew about the U.S. came from postcards and Hollywood movies. I was excited for my adventure, and eager to leave a war-torn China, but I did not know what to expect. There was definitely a great deal of culture shock when I arrived. There were only four Chinese students at my college. The bustle and lights of New York were like nothing I had ever seen, but I fell in love with the city, especially Broadway, and made friends with Chinese Americans in Chinatown.

While I did feel out of place some, I never felt unwelcome. The Americans I encountered were all kind and curious. They wanted to know more about me and my country and were happy to share their knowledge about my new home. I have many strong memories of conversations with people who had served in the Asia-Pacific during World War II, had fought alongside Chinese soldiers, and were now eager to help me.

For example, when I switched colleges to the University of Maryland, I met Captain George Fogg, who was the director of personnel. He had served in the Pacific theater during World War II and now took the Chinese students under his wing, helping them get settled and find housing or jobs. I also hitchhiked back to New York once and an older gentlemen who had fought in the war immediately stopped his truck and gave me a ride, sharing stories and buying me lunch.

Sentiments toward Chinese did not immediately switch when the Cold War started. People still remembered World War II. And while political persecution of those with any supposed ties to communism did increase, I did not personally experience that translating to day-to-day prejudice against Chinese. Of course, I did still experience racism. And after the Korean War, I did come across individuals who chose to blame me for lost loved ones or their own personal experiences fighting overseas. Mostly, though, those I encountered either had positive feelings toward China due to World War II service or missionary childhoods, or knew very little of the country and were curious.

The shift was more gradual. As China grew and gained more attention and influence, the treatment of Chinese and Chinese Americans became increasingly tied to the state of the U.S.-China relationship. I continued to experienced racism based on ignorance and misplaced prejudices about Chinese culture. But, as mistrust toward China and the Chinese government grew, I also witnessed a growing mistrust toward Chinese Americans.

What is the atmosphere like today? The news is full of headlines about hate crimes targeting Asian, and especially Chinese Americans. How does the current hostility compare to your experience during other periods of U.S.-China tensions — including when the two sides were actively at war in the 1950s?

The past year has seen anti-Asian racism grow to levels I don’t think I have ever experienced before, at least not in such open and violent ways.

On the one hand, a growing pandemic originating from China started circling the globe, creating fear and panic. People were looking for someone to blame – anger at an outside force was much easier to deal with than the feelings of helplessness over a virus we were ill equipped to deal with. Tensions between the U.S. and China grew and the Trump administration stoked that anger. Little regard was given to how terms like “China Flu” and other strong racially tinged rhetoric would impact Chinese and other Asian Americans. It was much easier to take out fear and aggression on a Chinese American neighbor or the local Chinese business than on a government on the other side of the world.

At the same time, the U.S. was facing a different racial reckoning. Police brutality spurred demonstrations and the Black Lives Matters movement. The country was being forced to examine its racist institutions. The movement is an important and necessary one and I am glad it is happening. Anti-Asian racism, however, looks different than racism against Blacks. It has a different history and takes a different form. Tackling one does not immediately solve the other.

Unfortunately, the timing of the movement allowed strengthening anti-Asian racism more space to grow. As American society grappled with one form of racism, anti-Asian sentiment increasingly seemed to be a more palatable, socially acceptable form of racism. Anti-Chinese sentiment could be presented not as racism, but as nationalism. But, of course, that argument is fundamentally wrong. How is targeting other Americans nationalism?

Over the years, I have found that for Chinese Americans, people often forget “American” in favor of “Chinese.” A Chinese American’s family could have been here for generations, they could have never stepped foot outside the U.S., and yet their loyalty and American-ness will often still be questioned. During periods of tension and uncertainty especially, our differences are magnified and we are seen as outsiders.

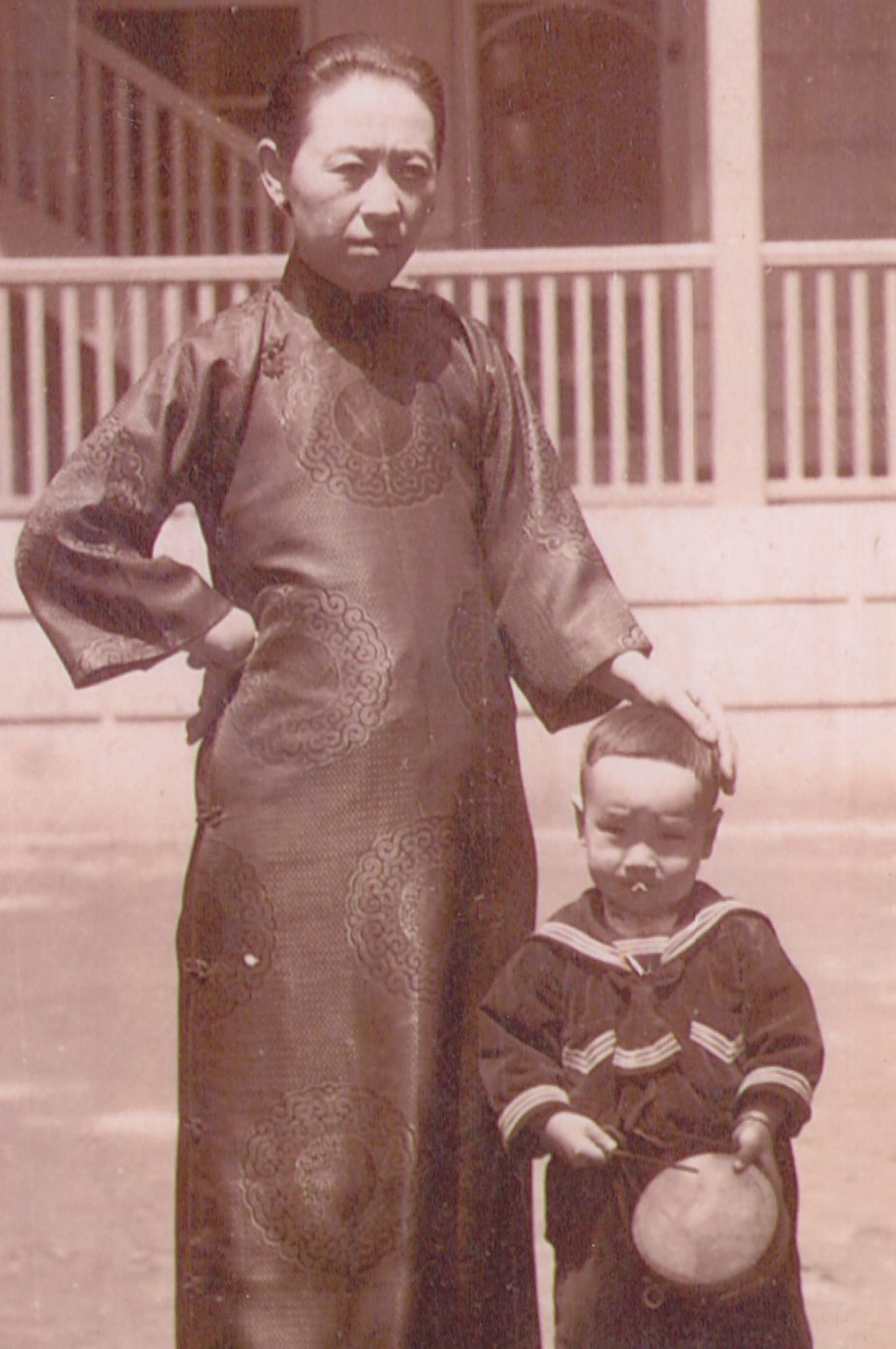

Chi Wang as a baby with his mother. Photo courtesy of Chi Wang.

Given the interconnectedness of U.S.-China relations today, it’s hard to imagine that after 1949, you had no way to return to China and few options to even communicate with your family in the country. What was that like?

When I saw the newspaper headline announcing the Korean War, I was shocked. I knew a lot had changed since I left China in 1949 – the People’s Republic of China was founded, the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan, and the world entered into a Cold War. But this was the first time I truly realized how different things had become. Given my own childhood experiences, China and the U.S. being at war seemed impossible. I distinctly remember crowding around a radio with my family listening to secret broadcasts reporting American victories against the Japanese. I cheered in the streets when the Allied victory was announced and crowded in with my fellow Chinese to welcome and thank the American troops as they entered Beijing. My brother had even served alongside them, having been drafted while at college in California. How could these countries who had fought, bled, and celebrated alongside each other not that long ago now be at war?

The war immediately cut us off from China. We no longer had access to wire transfers of money from back home. Luckily my school and the State Department offered assistance. It was also much more difficult to receive news from China. I was still able to receive infrequent letters from my family, through a friend in Hong Kong who acted as an intermediary. Still, contact was sparse and travel impossible. Neither of my parents ever had the opportunity to meet my wife, whom I married in 1958. In 1962, I received a letter informing me that my father had died two years earlier. I wouldn’t find out that my mother was killed by Red Guards in 1966 until I was finally able to return to China after Nixon’s visit in 1972.

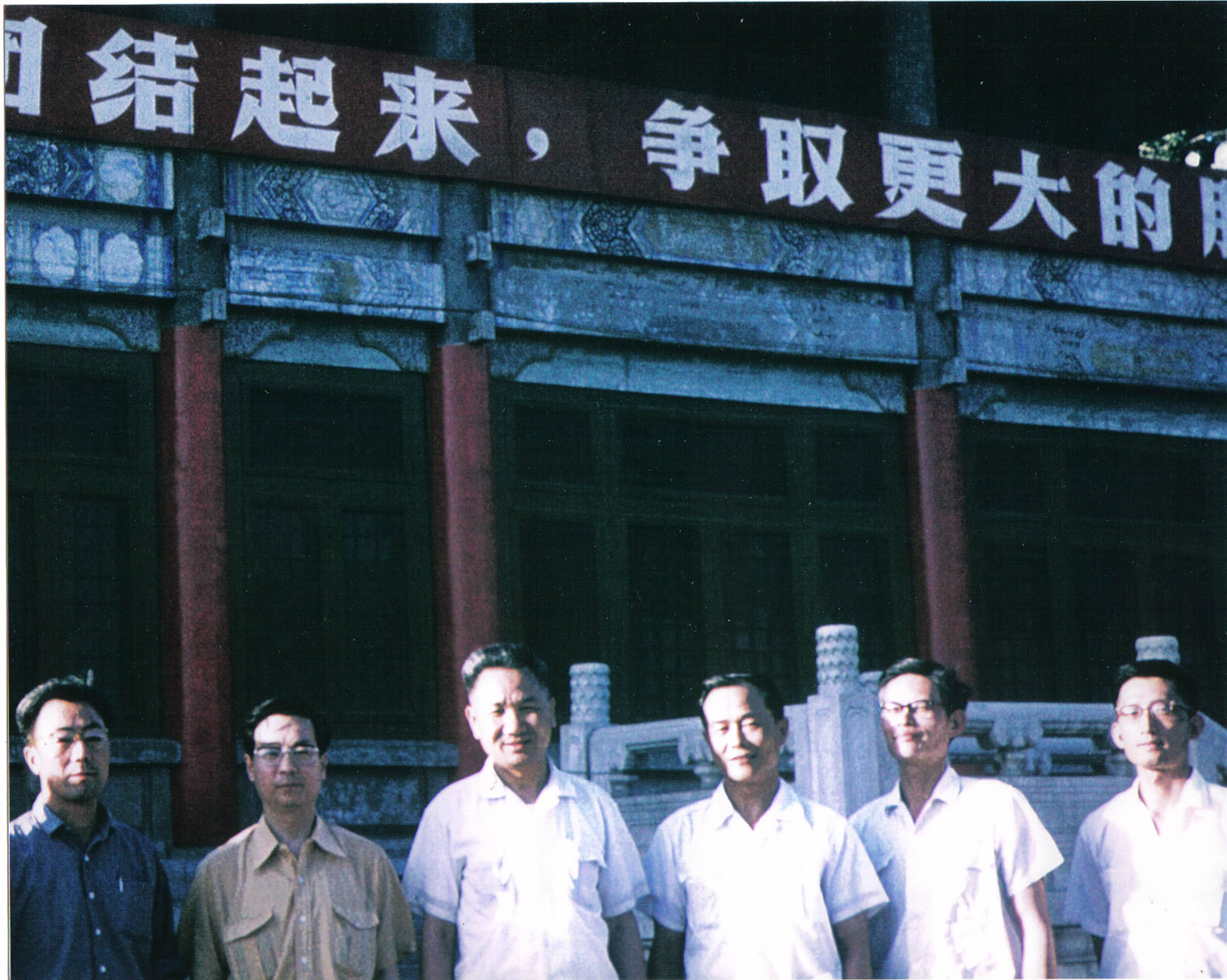

Chi Wang (second from left) visits the National Library of Beijing in 1972 to develop exchange programs. Courtesy of Chi Wang.

You helped lead some of the earliest scholarly exchange programs between the PRC and U.S. in the 1970s. What was the value of these people-to-people exchanges for the overall U.S.-China relationship at the time? And what role do people-to-people exchanges, which are coming under increasing pressure, play in today’s bilateral relationship?

It is easy to underestimate the important role people-to-people, scholarly, and other informal exchanges play in strengthening bilateral ties and encouraging mutual understanding. That would be a mistake. These interactions help set the foundation for more official ties and lay the groundwork for understanding. They fill in the gaps where other forms of diplomacy fall short and hold together the relationship when official channels are pressured or limited.

It was a ping-pong match that provided the opportunity for China and the U.S. to signal to each other that they would be open to the possibility of improving ties. And, after Nixon’s famous trip to China in 1972, it was people-to-people exchanges and other informal engagement that stepped up first, building ties, understanding, and trust while the governments slowly moved toward normalization.

I had the great honor of being one of the first to travel to China on behalf of the U.S. government after Nixon’s trip. I went to set up library and educational exchanges. The exchanges helped the two sides better understand each other and build avenues of communication and information exchange. After seeing how official engagement stalled after the Tiananmen Incident in 1989, Ambassador John Holdridge, Ambassador Arthur W. Hummel, Jr., and I realized that the need for such exchanges was even more apparent during times of official tension. We founded the U.S.-China Policy Foundation to help address that issue. When official tensions are high, informal exchanges keep communication open, help combat misconceptions, and build understanding.

(L to R) Ambassador Arthur Hummel, Jr., Ambassador John Holdridge, Ambassador James Sasser, Dr. Chi Wang, 1997. Photo courtesy of Chi Wang.

There was a major dearth of U.S. scholarship on China in the 1970s, due to the difficulties of accessing source materials coupled with arguably lower interest in general. Today, do you think U.S. policymakers and diplomats have a more detailed understanding of China compared to their predecessors?

During the Cold War, it was difficult to get information on China, especially as the Cultural Revolution closed off China even further. Despite the lack of access, however, there was a growing push from the academic community in the late ‘60s to learn more about China. John K. Fairbank from Harvard and John Linbeck and A. Doak Barnett from Columbia were leaders in this movement. Organizations pushing for increased engagement with China started being formed. I remember attending the founding conference for the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations in 1966. Over 100 individuals converged in Washington, D.C. to participate, including some, like O. Edmund Clubb, who had previously fallen victim to the Red Scare. In 1968, the Center for Chinese Research Materials opened and the Committee for the Scholarly Communication with Mainland China was founded.

There was an acknowledgment among scholars that a deeper understanding of China was necessary to better inform the U.S.-China relationship. As rapprochement began, that sentiment only grew and was shared by the White House administration at the time. If the U.S. had better been able to understand China’s relationship with the Soviet Union and been aware of the Sino-Soviet split, for instance, rapprochement might have happened sooner.

The old China hands who were so instrumental in building the U.S.-China relationship, essentially from scratch, are now mostly gone. Harvard’s Ezra Vogel just passed away in December. The current generation of policymakers and their advisors did not have the same interest in China and in increasing understanding as their predecessors. I hope that the following generation of experts, whose interest in China grew after the 2008 Beijing Olympics and who have a better grasp on today’s China, will start to gain prominence instead.

It’s become a truism to refer to the current state of relations as being at a “historic low.” As a history professor — and someone who has experienced much of the history of US-China relations firsthand — how accurate is this perception? Are we in uncharted waters for U.S.-China relations?

China is a different China than it was 50 years ago. It is different than it was even 10 years ago. U.S. policymakers, however, are failing to fully understand China today or adapt its policies to better fit the current global climate. Without having a clear understanding of China’s government, motivations, and priorities, mistrust and tensions between the U.S. and China will only grow.

In both the U.S. and China, domestic optics and talking tough have been increasingly prioritized over diplomacy and actual outcomes. This was especially seen during Trump’s presidency, but, so far, the strained relationship has continued under the Biden administration. The harsh language used to appeal to audiences back home only breeds further mistrust and makes it more difficult for the two sides to address substantive issues or come to any sort of consensus.