This is second entry in John Van Fleet’s Shanghai Lockdown Diary in The Diplomat. Read the first here.

Xujiahui, Shanghai, April 26: We knew almost no one in this high-rise of 31 stories, 90 units, and more than 200 people, until March 29, the first day of our building’s lockdown. (We got a head start on the rest of the city because they found a case in our building – lucky us.) Until then, few neighbors said more than to each other than the occasional “ni hao” exchanged in the lifts or the lobby.

What a difference a lockdown makes. The sociological transformation of this building in the past several weeks has been profound. We’ve bonded and worked together to get ourselves through these weeks, living in what may be the world’s largest sociological experiment – a Petri dish the size of a medium sized country. Our building residents have become a tribe.

And how quickly we reverted. Facing lockdown and a collapse in food delivery, we rapidly became hunter-gatherers, seeking out food wherever we could find it, negotiating to get it back to each of our “caves,” inside a vertical warren of them, sharing tips and collaborating with other tribe members.

But unlike Stone Age tribes, ours exists almost entirely on WeChat, China’s version of Line or WhatsApp. As of three weeks ago, I feel I can rely on my tribe members for important things in my life, but I’ve rarely if ever seen them, let alone had a voice conversation with them. We live in a WeChat world, a text-heavy version of the metaverse, with gifs, jpgs, and links. We are digital hunter-gatherers.

One of Shanghai’s modern-day “cave dwellers” emerges, briefly, to bring food inside for her family, thanks to a group buy with her digital tribe. Photo by J. Van Fleet.

Our tribe developed organically and rapidly to meet the urgent need. On the day that we were locked down, someone put a QR code on the entrance door to our building, an invitation to join the WeChat group. We grew to a community of 160-plus within a day or so.

Tribes must adapt to survive – our ancestors had to adapt to ice ages. Our tribe developed first to share information primarily about pending food crises, as well as such things as nucleic acid testing times. Then, when group buying became almost the only way to get food delivered, three weeks ago, we evolved a leader for group buying for the entire compound (seven buildings), and one for each building, and sub-leaders to focus on various types of food. We call these leaders tuanzhang, which can mean “group head,” but in military use means “colonel.” Tuanzhang leading the (digital) efforts to procure food have become instant heroes in every corner of the city, WeChat warriors for their tribes.

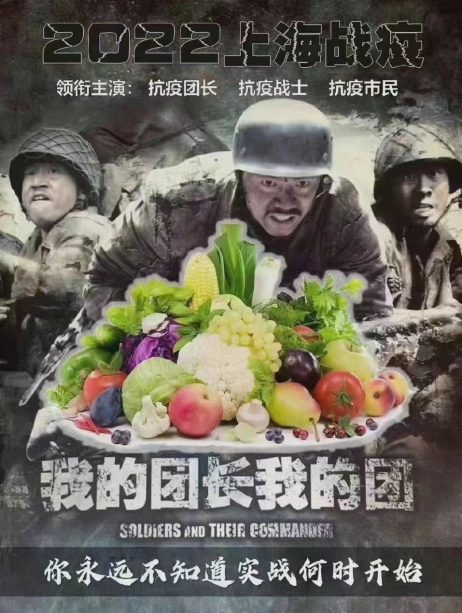

Image 3: One of the tsunami of social media memes, a movie poster takeoff showing a tuanzhang and his squad fighting for fresh produce. The movie title plays on “Oh Captain, My Captain!”, and the bottom caption says, “You never know when the real war will start.” The poster would be even more on point if the soldiers brandished smartphones and were female. Image from Chinese social media.

And they are often women, which should be intuitive. Last week, Shanghai publication Sixth Tone interviewed Sun Zhe, “a sociologist who has spent 15 years studying Shanghai community organizations.” He told Sixth Tone, “The rise of tuanzhang is closely tied to the more active role of women in their communities. If a community only has one WeChat group, it’s likely to be for mothers, since parenting has a strong communal aspect: You need to know about the community’s security situation, be familiar with the nearby supermarkets, and keep up to date on issues like food safety… Mothers also tend to play a more direct role in the care of the elderly and better understand the needs of older people.”

One more sign of our regression: Barter has become pervasive. At first, staples such as fresh vegetables and fruit and milk commanded an exchange premium, and one media wag suggested that Coca-Cola is practically hard currency in Shanghai right now (sorry, Pepsi). As food supply has become a bit more reliable in the past two weeks, thanks in large part to our (women) warrior tuanzhang, the barter economy has become a bit less visible.

Another aspect of our current situation that catches my attention: our volunteers. We have several in our building. One, a lawyer by profession, has taken the substantial responsibility to be the xinxi yuan – yes, we now have a name for the role – an information screener and a conduit between us and our neighborhood committee. These are elected but non-paid representatives of our area who interact with the government directly.

An entire family of residents, the Zhangs, have been spending hours per day supporting our tribe, primarily by organizing the almost daily testing, plus distribution of group purchases and other deliveries. Our tuanzhang are of course volunteers too. Volunteers have become the lifeblood of legion little tribes all around the city.

Their spirit pervades the tribe. Some senior citizens in our building don’t use apps well, or at all, and they’ve therefore been left out of the group buying skirmishes, so other residents have donated food to them. Others have small children who need extra milk, still others need medical attention. One resident couldn’t get to his regular chemotherapy treatment – the usual driver had tested positive – so another resident volunteered to chauffeur.

And we’ve had a few positive tests in our building. Those people can’t leave their units for any reason, so volunteers ensure that they get sufficient food delivered to their doors.

Image 4: Mr. Zhang and his daughter Iris as “big whites,” the nickname for those in hazmat suits, distributing antigen test kits to the rest of the building’s tribe (left), and checking us in for nucleic acid testing (right). Photos from I. Zhang.

The Zhang family in the Before Time. Photo from I. Zhang.

A number of us have wondered, in our WeChat group, what our situation would be like if we didn’t have a digital platform for communication within our tribe. During the Spanish flu epidemic 100 years ago, which also featured widespread quarantines, few had even telephones. Living like that, without any ability to communicate with neighbors, would make the situation we’re in now unfathomably worse.

We often hear that the advent of social media has been like rocket fuel for fake news, rumors, and the like. In our building, and throughout the city, we’re seeing another effect of social media: the rapid ability to dismiss this sort of misleading information. Before such instantaneous group communication, we always lived in danger of the telephone game effect, with “information” passed from individual to individual gaining distortions with each passing. Now when an unfounded rumor gets posted to our building group, everyone sees it instantaneously, and someone with sharper eyes and properly tuned skepticism may be able to debunk it. It’s like having more control rods in a nuclear reactor. They slow the speed of misinformation fission. (This effect largely disappears when tribes form not because of physical proximity, or sheer necessity, but based on ideological affinity. In the latter case, confirmation bias often overwhelms rationality, and we suffer a chain reaction of chaotic misinformation.)

In a few weeks, this iteration of lockdown will pass. We can’t know how much these changes will affect us after the lockdown ends. Will we revert to our previous anonymity? Will the spirit of community cooperation gradually recede, like an outgoing tide?

In thinking through these questions, I’m reminded of “The Shelter,” an episode of the 1960s television program “Twilight Zone” that continues to resonate through the decades. In the episode, the residents of a city block in an Anytown, USA, experience panic as a nuclear attack seems imminent. The threat utterly transforms them, in that case for the worse – they become sort of a suburban, middle-class, and adult version of the boys in “Lord of the Flies.” Once the threat has passed (a false alarm), the neighbors are eager to resume their pre-threat, happy-go-lucky ways – except one neighbor, who suggests that they can never return to their previous lives.

I think we may be in a similar situation, but with the change in a positive direction. I would guess that this rubber band doesn’t snap all the way back. I infer that tribes all around this city share our tribe’s experience, and that the community bonds forged by this shared crisis will not easily disintegrate. We will leave behind our digital hunter-gathering, but we will keep something from the experience.

Image 5: Two “big white” volunteers taking a break from distributing those white Styrofoam boxes filled with food, one of the government distributions. Photo by J. Van Fleet.

It’s often said that China’s urban communities lag behind their urban counterparts in the more developed world in volunteerism. Whether or not that’s true is an open question. Iris’ mother has for years volunteered a few times per week at a local hospital, in the oncology ward for children. But whatever the baseline of volunteerism in Shanghai may be, I think that it will surely rise as a result of these weeks of lockdown. Sun, the sociologist, told Sixth Tone, “I think that these ‘communities of common destiny,’ as some might call them, will remain even after the outbreak is brought under control.”

Our tribe isn’t representative of the people of Shanghai, just as Shanghai isn’t representative of China. We’re in a relatively better-off section of town, with an array of resources available that people in less well-off areas, or gig or migrant workers, or temporary employees, or people with medical conditions, numbering in the millions, do not have. Those people are suffering, some of them dying, from this lockdown, which a broad swath of experts say has been worse than the risk it purports to address. So any communal bonds that have grown through this crisis, and that may linger after it passes, are probably essential for the city’s healing.