The United States and its allies are in a strategic quagmire. Buffeted along the full spectrum of hybrid warfare by peer, near-peer, and nonstate adversaries, they are challenged in every domain of contemporary conflict. Russia’s Ukraine invasion upended the already threatened liberal, rules-based order and down-shifted expectations about the behavioral boundaries within which states might act. China’s unprecedented rise as an economic, technological, and military rival has catalyzed a tectonic shift in the global balance of power. The revival of Sino-Russian alignment further complicates the West’s strategic predicament.

Arguably the U.S. and its allies have not crafted a grand strategy for geostrategic competition since containment and mutual assured destruction forged the bipolar world of the late 20th century. In recent years the collective Western strategic disposition has been reactive, never proactive, and rarely strategically effective.

Today a new grand strategy articulating an enduring strategic vision is desperately needed to meet not only the military threat posed by Russia, but the more comprehensive threat – economic, technological, military, and indeed ideological – from China.

What is the Solarium Project?

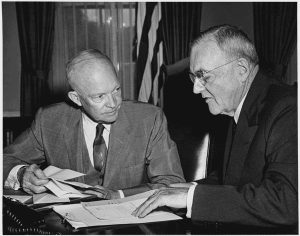

In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower recognized that the United States lacked a grand strategy for combating global communism. He wanted to defeat it and recognized the need for a grand strategy to achieve that goal.

To meet the challenge, Eisenhower initiated Project Solarium, named for a room in the White House. He created three task forces from a bipartisan community of national security experts. Bipartisanship was critical since a grand strategy integrating all the elements of national power would require support throughout the political class and the nation. The task: Present recommendations for a grand strategy to defeat communism.

In the end Eisenhower opted for containment, advocated by George Kennan. The strategy consisted of three complementary aspects. The Atlantic Alliance would oppose any Soviet effort to expand its territory. It would fight to discredit and de-legitimize Communism as a failed ideology. It would offer a democratic political system and a rules-based international order as a positive alternative.

A New Solarium

A modern Project Solarium could forge a new grand strategy designed for today’s global threat environment. Input and support from both parties in the United States, as well as U.S. partners abroad, is essential to preserve continuity between administrations. The strategy should define our enduring, shared interests, the global threat environment, and viable strategies to respond to the most pressing threats. A New Solarium project should evaluate competing approaches to today’s challenges.

Even with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there is broad consensus that the longer-term, and more existential challenge to the liberal, rules-based world order is from China. We need to define what relationship we desire with China, and what is in our best interest. We need to ask: Is China a competitor or an enemy? What end-state is desired? Are we seeking to divide the world into spheres of influence, in which, for example, China is pre-eminent in Asia and the West pre-eminent in Europe? How would that work? Do we want to contain Chinese economic or territorial expansion, or do we want to defeat China’s efforts to become a true global superpower?

It is precisely the task of a New Solarium to determine the most viable strategic courses we might adopt; however, to advance the conversation we envision these three most obvious strategic options for discussion; 1) Defeat China, 2) Bifurcation, and 3) Managed competition. Each of these has its advocates and critics; each has advantages and disadvantages.

Strategy 1: Defeat China

China’s economic growth over the past several decades has been both impressive and alarming. Its growing military power and stated design to resume its historical position of global dominance by 2049 justify a robust retaliatory strategy to defeat China and deprive it of its strategic objective, like the Cold War containment strategy.

A grand strategy along those lines would seek to isolate and contain China, treating it as an adversary or enemy, and in concert with partners and allies, move aggressively to challenge its global initiatives, claims to the nine-dash line, and claims to extended fishing and mineral rights; counter its economic coercion and debt traps; and expose Huawei and other Chinese commercial juggernauts as tools for espionage.

The West would aggressively move to discredit and de-legitimize China’s 2049 vision of global dominance and reverse China’s recent diplomatic, information, and economic gains in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America, while limiting China’s growth potential within Asia. It would seek to maintain the United States’ position of military dominance in Asia, by reinforcing the tensile strength of the first island chain links, and particularly the autonomy of Taiwan.

To defeat China the West must also engage its extraordinarily innovative collective private sector to win the race for dominance in the most critical technology areas such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, quantum technology, neuroscience, and others. The U.S. and its allies must accomplish demonstrable dominance such that China, like the Soviet Union in the 1980s, realizes this is a race it cannot afford and cannot win.

This strategy will recognize and exploit China’s intrinsic and organic weaknesses, such as its dependence on imported fuels, food and water vulnerability, and demographic challenges. It will attempt to prevent China from regaining the double-digit economic growth it needs to escape the middle-income trap.

If successful in these efforts, the West would be in a good position to defeat China in the diplomatic and information dimensions, as partners, allies, and neutral nations will see the benefits of alignment with the United States and the West. China would – in this scenario – be forced to accept the status quo of a liberal, rules-based world order under U.S. and Western dominance, with China as a powerful, but ultimately resigned, outlier.

Strategy 2: Bifurcation

This scenario envisions a bifurcated world with a Western alliance on one side, and a China-centric entente on the opposite. China is pursuing “the China Dream” to achieve global military and economic supremacy by 2049. It rejects a rules-based international order that respects democracy, freedom of the press, and other values the West embraces, but unlike Russia, whose ambitions are focused on its periphery, and contrary to Beijing’s public statements, China’s ambitions are global.

China claims it seeks merely to protect its sovereign territory. But its definition of what that territory embraces keeps expanding. In theory, the nine-dash line in the South China Sea represents the maximum of Chinese historical claims. Its aggressive marketing of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Huawei’s 5G infrastructure, the Thousand Talents programs, and its aggressive “Three Warfares” concept that employs economic, diplomatic, and political coercion, backed up by its military, more truly express its ambitions.

To achieve the “China dream,” China is betting heavily on new technology, including artificial intelligence, quantum computing, 6G, cloud computing, and computer processors designed and built within the framework of such policies as “military-civil fusion,” “Made in China 2025,” and “China Standards 2035.”

Western efforts over the past 30 years to engage and incorporate China within the liberal, rules-based world order have failed. China’s leaders have by now made it crystal clear they will not accept that role. The bifurcation strategy would recognize we are in a de facto Cold War 2.0. It would consist of a policy of containment; treating the China-centric entente as a unit and an adversary, politically, economically, and militarily; and being prepared should armed conflict erupt. This approach would echo limited elements of the Cold War containment policy, primarily to stop expansion of adversarial influence or territorial control.

The approach would be built on disciplined de-coupling of supply chains as well as cessation of trade with China. It would require a legislative and economic approach both penalizing private sector violators of the de-coupling policy, as well as incentivizing them to establish supply-chain autonomy and re-shoring production and manufacturing.

The bifurcation strategy acknowledges global spheres of influence for each bloc with the reluctant recognition that engagement is imprudent and reduces security. It would rest on an implicit agreement by both blocs not to interfere or encroach on activities within the other bloc.

Strategy 3: Managed Competition

The managed competition strategy accepts the multipolar world paradigm with Beijing and Washington each working to build strategic if fluid coalitions, competing for allegiance or at least alignment with Europe, India, and other powers. Like the bifurcation strategy, a managed competition approach acknowledges spheres of influence, but accepts their fluidity with opportunist nations either sliding between blocs or remaining neutral. Through economic, diplomatic, and informational efforts each bloc seeks to expand or strengthen its relative power and influence at the expense of the other.

A managed competition strategy would avoid armed conflict with China, but aggressively challenge and discredit such Chinese initiatives as the BRI while presenting competing ideas that are more attractive.

The managed competition strategy does not exclude commercial and financial interaction – even extensive interaction. Trade between the competing blocs will take place according to classic market principles such as comparative advantage, economies of scale, and gains from trade, with extreme caution and scrutiny in industries that impact on national or international security. Cooperation would be possible on such global issues as climate or pandemic management, though China has clearly shown that even regarding such global challenges it will always subordinate collective interest to national interest.

In this scenario, the West will challenge Beijing’s efforts to employ economic or other coercion to silence criticism of China. It will impose retaliatory punishments for Chinese conduct that undercuts national sovereignty or trust in political or social institutions. The managed competition strategy will support and assist allies as they build their own military capabilities and work to integrate those capabilities. China is paranoid about being surrounded or isolated, so planning for this scenario must factor in Chinese reactions and how to address them.

In a managed competition scenario, we work aggressively to find areas of common interest with China to minimize tensions, while protecting U.S. interests such as intellectual property rights and a level playing field for trade. We treat China as a competitor and rival rather than an enemy, without ceding primacy in any geographical region, using alliances to counter Chinese economic or military expansion. We aggressively compete with China for influence in the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the Americas, while discrediting and de-legitimizing its 2049 vision.

Every administration confronts serious challenges; however, today’s complex and intractable challenges appear to exceed the current bureaucratic methodology that has given us the anemic national and alliance strategies of the past several decades. It would be the role of a new Solarium to clearly define the strategic challenges, our strategic objectives, and viable, credible strategies for attaining those objectives.

The three example options described above are simple, obvious, and have been widely discussed; hopefully a new Solarium would produce more innovative strategic options. Whatever options emerge from a new Solarium, ultimately the key decisions regarding national grand strategy must be made by the president of the United States and his allied and partner counterparts. And even with bold national and international leadership, the actual implementation of any strategy will depend on legislative branch leaders who put nation above party.

Even with these caveats taking a leaf from Eisenhower, the U.S. government – for both this or any succeeding administration – would profit greatly by assembling the kind of diverse, bipartisan team that made Project Solarium a strategic milestone on the road to strengthening U.S. national security and paving the way for the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union. We need a new Solarium now, more than ever.