Officials in Beijing are rolling out the red carpet for visiting VIPs from Europe.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was the first Western leader to make a post-pandemic trip to China, traveling there in November 2022. This led to criticism from senior figures within his coalition government, who said he should have waited until a strategy on China had been agreed upon between the parties.

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón went to Beijing on March 31, 2023, where he was met by President Xi Jinping, as well as China’s chief diplomat Wang Yi and the recently appointed foreign minister, Qin Gang.

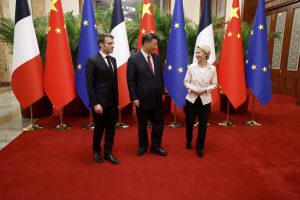

The three men turned out again to welcome Ursula von der Leyen, the head of the European Commission, who went to the country along with French President Emmanuel Macron and his foreign minister, Catherine Colonna. They arrived on April 5 for a three-day visit. The first meeting on the agenda was a bilateral between Xi and Macron.

Speaking in front of reporters in Beijing, Macron said they would discuss Ukraine.

Macron told Xi: “I know I can count on you … to bring Russia to its senses and draw everyone back to the negotiating table.”

Xi has been promoting a policy document entitled “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis.” He claims he can broker talks between the two sides. Yet, although Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin are in frequent close dialogue, the Chinese leader has not recently made contact with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

“This is clearly a charm offensive on the part of the Chinese,” says Hanns Maull, senior associate fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin.

“China is courting European governments and the European Union. It is hoping to revive the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between the EU and China, which has been put on ice. China also believes that through an improved relationship with the Europeans, it can loosen their transatlantic ties to the United States and split the West,” says Maull.

Such a strategy is a major concern in the White House. U.S. President Joe Biden briefed Macron on U.S. foreign policy before the French president departed for China.

The two leaders spoke by telephone on April 4 and, according to a White House readout of the conversation, Biden and Macron “reiterated their steadfast support for Ukraine in the face of Russia’s ongoing aggression.”

Maull from the Mercator Institute notes that Macron has repeatedly expressed the hope that he can persuade China to be a moderating influence on Russia.

“This is not a view shared by everyone in the EU, although other leaders will not publicly object to Macron making such an effort,” says Maull.

In his view, there is little the Europeans can do to bring about a shift in the Chinese position. “The recent meeting between Xi and Putin in Moscow proved that China has no serious intention of constraining Russia. China tries to give the impression it is playing the role of a neutral peace-maker, but so far it has not stopped the fighting,” says Maull.

EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell plans to go to China in mid-April. Borrell takes the view that “China has a moral duty to contribute to a fair peace and cannot side with the aggressor.”

He insists that China’s “position on Russia’s atrocities and war crimes will determine the quality of relations” between the EU and China. Borrell expressed his opinion at a joint news conference with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, following a bilateral meeting in Brussels on April 4.

At the media event, Blinken insisted that “the United States and the EU continue to work in lockstep, together with a broad coalition of partners around the world, to ensure that Ukraine can defend itself, its people, its territory and the right to choose its own path.”

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen tends to align with the U.S. view that China represents a security challenge. Before her trip to Beijing, von der Leyen gave a speech in Brussels in which she described China as pursuing “a systemic change of the international order.”

She quoted Xi’s comments during the 2022 Party Congress, during which he said that he wants China to become a world leader in “composite national strength and international influence” by 2049.

“To put it in simpler terms,” said von der Leyen, “he essentially wants China to become the world’s most powerful nation.” Like Borrell, she believes that Beijing’s interactions with Russia will determine the future of China-EU relations. She has criticized Xi for maintaining his friendship with Putin and dismissed China’s proposed political solution to the Ukraine crisis, stating that any plan which consolidates Russian annexations is “simply not viable.”

Maull believes that von der Leyen is able to speak more bluntly than European heads of government because of her unique position as president of the European Commission. “Cleary, she’s trying to assume a leadership role. However, there are different voices even within the Commission, let alone the Council, and let alone among the member states. So it’s a complicated situation,” says Maull.

Chinese state media seized upon the positive aspects of the exchanges between Xi and Macron. Xi described China and France as major world powers that have the “ability and responsibility” to overcome their differences and safeguard world peace.

In return, Macron said “we must not disassociate ourselves or separate ourselves from China,” adding that France would “commit proactively to continue to have a commercial relationship with China.”

Macron was accompanied by a business delegation of more than 60 executives from French enterprises, including Airbus, Electricite de France and L’Oreal, with many seeking more cooperation with China.

Despite the clout yielded by the business lobby, Professor Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute in London, says that Marcon’s sway over Xi in the political sphere is limited.

“I don’t think Xi Jinping will care enough about either France or the European Union to defer to them and do what they say, even if they speak in a coordinated way. Xi talks about making peace, but he is still very much supporting Putin,” he says.

Nevertheless, Tsang believes that the “divide and rule” approach — through which China attempts to split the Europeans and the Americans — is unlikely to succeed.

“The Europeans are much closer to the frontline in Ukraine than the Americans, so China’s partisan, pro-Russian approach does not go down well in European capitals,” says Tsang.

For Tsang, the idea of a charm offensive rings hollow. “This is a charm offensive by a wolf warrior, and so there are limits to how charming you can be.” He is also unimpressed by China’s peace-making efforts, which have not led to any shuttle diplomacy between the combatants. “The absolute bare minimum that Xi could do is to agree to have a virtual meeting with Zelenskyy, but that hasn’t happened yet,” notes Tsang.

In Maull’s assessment, the great challenge for the EU is to find a practical modus vivendi — a feasible arrangement that works in a multipolar world.

“The United States finds it very hard to adjust to a situation where it is no longer the unchallenged number one, while China finds it very hard to accept that it should not be regarded as the unchallenged number one,” he says.