If that fateful day hadn’t come, Yokota Shigeru and Sakie would have lived a run-of-the-mill family life, just like any other.

But 46 years ago, on the evening of November 15, 1977, their 13-year-old daughter Megumi suddenly disappeared on her way home from junior high school in Niigata City, which is about 250 kilometers north of Tokyo.

So began the anguish of the Yokota family. Their desperate efforts to search for their daughter is said to have been the largest in the history of Niigata Prefecture’s police department.

Sakie, now 87, told me that while she was living in Niigata after her daughter’s disappearance, the local police would call her to confirm whether dead bodies found in the snow were Megumi or not. She said she fell into a state of neurosis.

On January 1997, 20 years after their daughter vanished, the family was shocked to learn that North Korean agents had abducted Megumi.

The Yokotas, including Megumi’s twin younger brothers, Takuya and Tetsuya, 55, have since become Japan’s most famous crusaders for Japanese abduction victims. Yokota Megumi remains a tragic heroine for the Japanese abductees and for the whole nation.

North Korea claims that Megumi died in 1994, but her family believes that is a lie. She would be 59 years old if she is still alive.

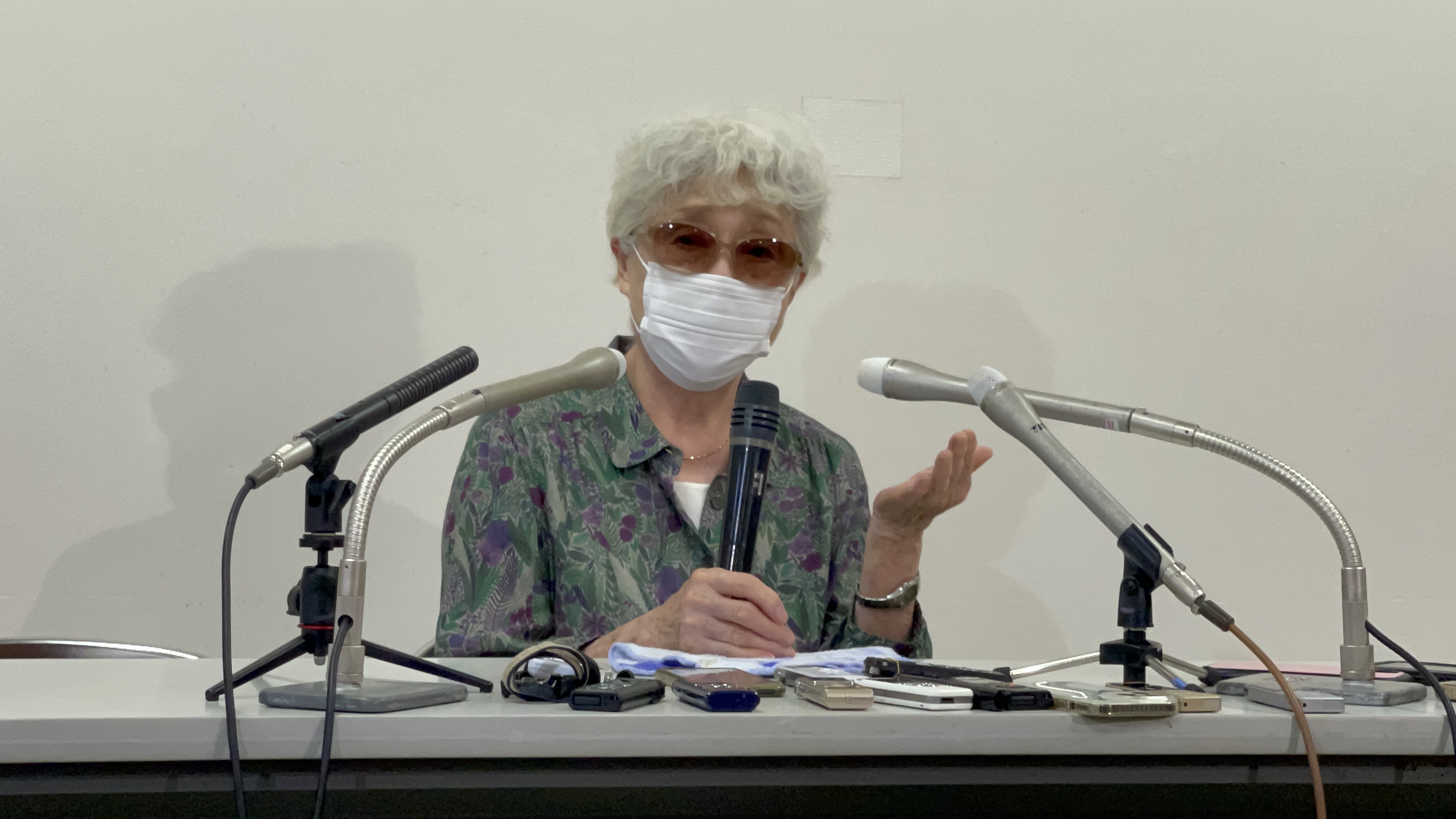

On November 7, ahead of the 46th anniversary of Megumi’s abduction, Sakie held a press conference at her condominium in Kawasaki City, adjoining Tokyo. She called on Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio to hold a summit with North Korea’s supreme leader Kim Jong Un to bring back Megumi and other Japanese nationals abducted by North Korean agents.

“There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think about Megumi-chan. Every morning when I wake up, I ask her how she’s doing on my own, and I talk to her father’s photo,” Sakie said. (Chan is a Japanese honorific added to children’s names to convey affection.)

Yokota Sakie holds a press conference at her apartment in in Kawasaki City, Japan on Nov. 7, 2023, ahead of the anniversary of her daughter’s abduction. Photo by Takahashi Kosuke.

Shigeru, Megumi’s father, died in June 2020 at age 87 without ever being reunited with his daughter.

Sakie said she had received a phone call from Kishida as an inaugural greeting soon after the premier took office in October 2021. In return, she sent a letter to Kishida, asking him to visit North Korea as soon as possible and realize a summit with Kim.

Sakie strongly believes that in a dictatorial political and social system like North Korea, things can move quickly with a single voice from the supreme leader. Kishida can demand Kim’s bold decision, as Sakie is requesting.

In 2002, Kim Jong Il, Kim Jong Un’s father and predecessor as North Korean leader, decided to return five Japanese abductees after then-Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro visited Pyongyang.

When asked, “Is there any message you would like to send to Kim Jong Un?” Sakie answered by appealing to Kim’s love for his own daughter, who made her public debut last year:

I wonder if this message will really reach him. Mr. Kim Jong Un has often taken his own cute girl with him. When I see someone like her, I recall Megumi-chan’s narrow eyes and round face when she was little, and that cute girl looks a lot like Megumi-chan. I can see how much you [Kim Jong Un] love and care for her. Our family shares the same kind of feelings you have now.

I want you to know that I am thinking of my child and waiting for her. My child was taken into a place from where your nation has never let her go, and she has been unable to come back for 46 years. I want you to understand how painful it really is. I don’t know if [Kim Jong Un] can surely understand this, but I always hope that I can deliver this message to him.

Although its efforts have failed to result in any more abductees returning to Japan since 2002, Tokyo has garnered international support toward the resolution of the abduction issue.

Most recently, on November 9, the South Korean Embassy in Tokyo jointly hosted a music concert with Asagao no Kai, a group comprising residents who live in the same apartment complex as Sakie in order to call for an early resolution to the abduction issue. This event itself highlighted the significant improvement in Japan-Korea relations.

“In South Korea, we also face the issues of abductees, detainees, and prisoners of war who have not returned [from North Korea]. To this day, North Korea still holds 516 South Koreans who were abducted after the war, while the number of wartime abductees is estimated to be around 100,000,” South Korean Ambassador to Japan Yun Duk-min said.

At the concert, violinist Yoshida Naoya, who was a classmate of Megumi at Yorii Junior High School in Niigata City, and pianist Kim Cheol Woong, a North Korean musician who defected to South Korea in 2001, performed to pray for the return of the Japanese and Korean abductees. Also in attendance were embassy officials from 15 countries, including U.S. Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel’s wife as well as the late former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s wife Akie.

The Japanese government confirmed that North Korea kidnapped 17 Japanese nationals in the 1970s and 1980s. In September 2002, when Koizumi visited Pyongyang, Kim Jong Il admitted for the first time that North Korean agents had kidnapped 13 Japanese nationals; Kim insisted the other four people in the Japanese government’s count never entered North Korea.

Of the 13 Japanese nationals North Korea admits that it kidnapped, five were returned to Japan; Pyongyang claims that the other eight, including Yokota Megumi, are dead.

North Korea claimed Megumi committed suicide in March 1994 and returned to Japan a set of remains. But Japan said that a DNA test proved they could not have been her remains, and her family does not believe that she would have committed suicide.

While in the North, Megumi married a South Korean national and had a daughter, Kim Hye Gyong, whom the Yokotas were allowed to meet in Mongolia in March 2014.

The abducted Japanese nationals, including Megumi, are believed to have been forced to teach Japanese language and culture to North Korean intelligence agents for covert operations against South Korea. There is a widespread belief that in October 2002, Kim Jong Il released the only five abductees who had not trained spies or taken part in terrorist operations against South Korea. As the rest are believed to have more knowledge of covert operations, the North has hesitated to provide any information on them or release them.

Today, North Korea insists that the issue of its abduction of Japanese nationals has been already resolved. Pyongyang appears unwilling to address the issue any further, partly because its bilateral relationship with Tokyo is simply not as important as it once was.

More importantly, there is widespread speculation that Japanese politicians may not actually want to move the issue forward because they believe that North Korea is telling the inconvenient truth: Megumi, and some of the other kidnapping victims, are dead.

However, North Korea’s notorious lack of transparency and long track record of obfuscation make it difficult to parse fact from fiction. The Japanese government should conclude the fate of the abductees through its own verification.

In the meantime, family members of the victims, like Yokota Sakie, will continue their decades-long wait.