I visited Shenzhen, one of China’s four largest cities, last week for the first time in five years after the COVID-19 nightmare. I most marveled at how dramatically the city has changed. I was particularly surprised by how widespread electric vehicles (EVs) have become and how high-tech those cars have become in such a short period.

Because of reduced exhaust gas emissions brought about by EVs, I felt the air in Shenzhen was as clean as that in Tokyo.

The overall penetration rate of new energy vehicles such as EVs and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) in Shenzhen has already exceeded a whopping 60 percent, making the southern Chinese city of more than 17 million residents the number one city for new energy vehicles in the world, according to a Chinese report.

What is the reason for the popularity of EVs in Shenzhen? For one thing, Chinese battery and automotive giant BYD, which has overtaken Tesla to become the world’s top EV maker by sales, has its headquarters in Shenzhen, which is a leading global technology hub due to its entrepreneurial and innovative culture.

For another thing, in Shenzhen, both the public and private sectors have worked together to promote the spread of EVs earnestly. Shenzhen is the first city in the world to go all-electric on buses in 2017. One year later in 2018, it also achieved 100 percent electric taxis. In addition, EVs have the advantage of being able to use temporary on-street parking for free for two hours every day.

The Chinese government announced a policy to promote the spread of new energy vehicles such as EVs in 2009. A sales subsidy system was fully implemented from 2010 to 2022. According to Chinese media, the total amount of subsidies disbursed by the government is said to have reached 300 billion yuan ($41.4 billion).

During my four-day stay in Shenzhen, I had the opportunity to ride many times in a compact EV, the BYD Dolphin, owned by a Chinese friend of mine.

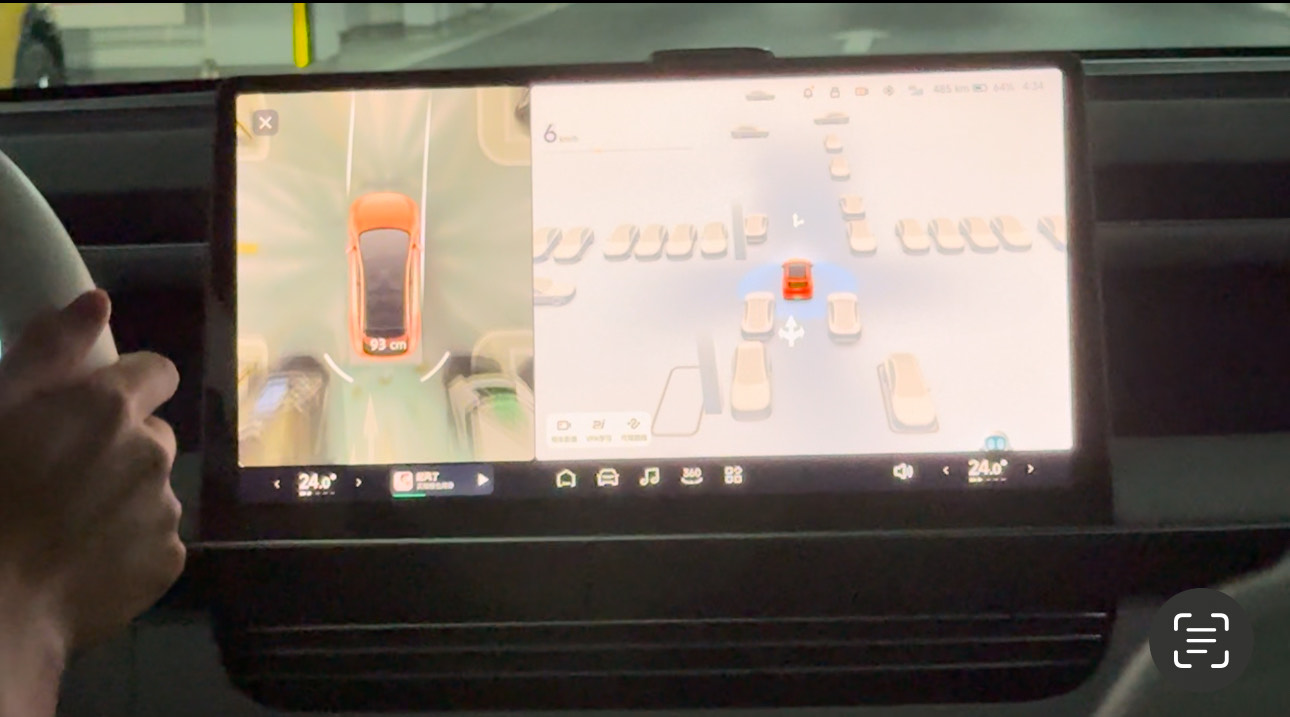

The friend said he bought the car several years ago for 120,000 yuan ($16,570). The car navigation screen is quite large, and it displays an image of your car as if it were taken from directly above by a high-performance camera. Of course, there are no cameras in the air directly above the car; instead the images are created and displayed using sensors inside the car. The same system is used in taxi navigation systems.

My friend emphasized the low electricity bills of EVs. He said he commutes 30 km to work every day, and his electricity bill is just over 2 yuan ($0.28) per day. He said that his monthly bill is only 80-100 yuan. In contrast, his previous Toyota Highlander SUV cost a little over 1 yuan per kilometer.

While I was in Shenzhen, I also had the opportunity to ride in Chinese electric vehicle maker Xpeng’s latest electric SUV model, the G6, which costs 276,900 Chinese yuan.

This car’s navigation system displayed nearby cars, building pillars and other small objects, as well as people moving around the car.

The navigation system in use in Xpeng’s latest electric SUV model, the G6.

My friend demonstrated the G6’s self-driving function on the Shenzhen highway, which was my first experience in a self-driving car.

In addition, when entering the vehicle, the camera takes a picture of the driver’s face and authenticates the individual. If the person is registered, the car can be unlocked using the keyless system.

China became the world’s largest exporter of automobiles in 2023 for the first time, knocking Japan off its perch thanks to strong overseas sales of EVs. It was the first time in seven years that Japan had fallen from the top spot.

Japan’s auto giant Toyota has pursued the “carbon neutrality multi-pathway strategy” and has not abandoned its all-round strategy of working hard on gasoline cars, hydrogen cars, hybrid cars, and EVs. The pretense was to protect Japan’s strengths and jobs.

Other major Japanese automakers also stick to past successes and cling to vanishing assets like gasoline engines. As if to clearly show the lack of flexibility in the Japanese automobile industry, Japan’s transport ministry on June 3 announced the nation’s five vehicle makers – namely Toyota, Mazda, Yamaha, Honda and Suzuki – have admitted to falsifying performance tests to get certification for their products. It said all five companies uncovered the misconduct while carrying out a government-ordered internal probe.

Seeing the spread of electric cars in Shenzhen made me keenly aware of Japan’s inability to keep up with the full-scale shift to EVs around the world.

Meanwhile, China has not only become the world’s largest automobile exporter, but also established itself as the world’s largest market for EVs.