What was perhaps more surprising than the passing of centenarian U.S. President Jimmy Carter just days before 2025 was President-elect Donald Trump’s unexpectedly complimentary tribute. Despite once deriding the one-term Democratic commander-in-chief as “the nation’s worst president,” Trump eulogized Carter as “a truly good man” who “will be greatly missed.”

Despite a history marked by a barrage of insults and mutual disdain, the 39th and 45th U.S. presidents found common ground – if not outright agreement – on China. And Carter’s enduring legacy in China-U.S. relations is poised to influence Trump’s China policy across economic, military, and diplomatic dimensions.

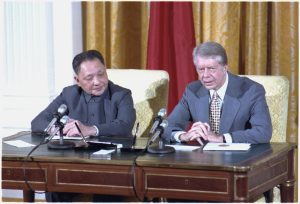

While Republican President Richard Nixon is often credited with “opening” relations with communist China, it was Carter who achieved the critical breakthrough. Shortly after taking office in 1977, Carter signaled his commitment to normalizing relations with Beijing. Two years later, he fulfilled this promise by formalizing full diplomatic relations and granting China “most favored nation” trade status. These steps significantly boosted China’s economy and created jobs, with bilateral trade doubling within a year.

Even after his presidency, Carter remained deeply involved in fostering China-U.S. relations, promoting people-to-people exchanges and improving living conditions for disabled people in rural China. His expertise on China even led Trump to seek his advice.

Yet, how could Jimmy Carter – a president renowned for his moral compass – leave a legacy that could influence Donald Trump, a figure often seen as his opposite, on China policy?

As surprising as it may seem, the answer lies in their shared perceptions of China’s role in the U.S. geopolitical grand strategy and how to advance U.S. interests in dealing with the country, albeit from differing angles. Economically, Carter agreed with Trump that China was “getting ahead” of the United States. However, during a 2019 phone conversation with Trump – at the height of the China-U.S. trade war – he also emphasized that China’s avoidance of wars had allowed it to focus on economic development, positioning it to surpass America.

Months after their conversation, the Trump administration secured the Phase One Trade Agreement with China to ease the trade war. While it is unclear whether Carter’s words directly motivated Trump to pursue economic rapprochement with Beijing, Trump’s praise of Carter’s letter on China as “beautiful” and his positive remarks about their phone conversation suggest that Carter had a certain level of influence on Trump’s decision.

Although Trump appears poised to escalate tariffs on Chinese imports in his second term, he is also extending olive branches to Beijing by opposing the TikTok ban and inviting Xi Jinping to his inauguration. Reflecting on lessons from his first term, Trump may have recognized that another trade war with the world’s second-largest economy could ultimately backfire. Instead, his economy-focused “China model” is likely to guide him toward negotiating with China to achieve economic détente, with his hawkish posturing serving as a tactic to secure bargaining chips.

On the military front, both Trump and Carter expressed intentions to end wars and promote peace, albeit likely for different reasons. During their conversation, Carter contrasted a war-free China with a warlike United States, stressing that China’s avoidance of conflict since the normalization of China-U.S. relations in 1979 allowed it to allocate resources to projects like high-speed rail rather than military spending. Carter suggested that if the United States had invested less in wars and more in domestic infrastructure, the country would not only be in a stronger fiscal position but also have better infrastructure, welfare, and education systems.

This perspective aligns with Trump’s “America first” philosophy. Although U.S. military spending grew steadily during Trump’s tenure, it remained significantly lower – when adjusted for inflation – than during Obama’s first term. Trump himself criticized current defense spending as “crazy” and repeatedly called for the return of U.S. troops while denouncing military interventions as costly and ineffective. Even amid rising concerns about an arms race and a potential cold war with China, Trump still pursued multilateral arms control negotiations involving Beijing and Moscow.

If anything, Carter’s suggestions likely reinforced Trump’s view of China as more of an economic superpower than a military threat. While Trump is unlikely to make substantial cuts to U.S. military spending, he may pursue alternative strategies to reduce the economic burden of military engagement with China. One approach, already evident during his first term, involves pressuring Indo-Pacific allies – such as Australia, Japan, and South Korea – to contribute more to their defense partnerships with the U.S. However, this strategy risks undermining U.S.-led alliances like AUKUS, potentially jeopardizing their cohesion and effectiveness.

On the diplomatic front, Carter offered Trump a compelling example of advancing U.S. interests through cost-effective diplomacy. Beyond Carter’s moral and ethical motivations for normalizing China-U.S. relations, an important geopolitical calculation was his prediction that China would become a major global player. Therefore, he sought to drive a wedge between Beijing and Moscow, thereby weakening the cohesion of the communist bloc.

Trump appears to be drawing inspiration from Carter’s approach by seeking to fracture the China-Russia partnership. He has highlighted underlying tensions between the two nations, referring to them as “natural enemies” due to China’s interest in Russia’s resource-rich Far East. Early indications suggest that Trump may pursue this strategy by reducing tensions – and even improving ties – with Moscow to exert pressure on Beijing.

A potential spillover effect of this strategy is progress toward Trump’s goal of denuclearizing North Korea – an objective he pursued but failed to achieve during his first term. With China cautiously balancing its position between Russia and North Korea, any potential split between Beijing and Moscow could weaken the cohesion of the Beijing-Moscow-Pyongyang relationship. Gaining the support of either China or Russia would be instrumental in opening new opportunities for public or back-channel diplomacy with Pyongyang on nuclear weapons.

Despite stark differences in their political philosophies, the underlying logic of Carter’s and Trump’s China strategies suggests that Trump may adopt a more nuanced approach to Beijing in his second term. Even his loyal Cabinet, while hawkish in rhetoric, may grant him the flexibility to maneuver more diplomatically in the Indo-Pacific, facilitating the negotiation of deals with China and other nations alike.