Former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates’ new book Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary of War has received a lot of attention, including from The Diplomat. Most of the attention has focused on Gates’ criticisms of Obama’s leadership, especially over decisions regarding the war in Afghanistan. Gates himself noted at the beginning of his memoir that the book was “of course, principally about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.” But Gates also oversaw the U.S. Defense Department under two Presidents right as American concern over China’s military rise began to reach a fevered pitch. What does his memoir have to say about U.S.-China military relations?

Gates’ memoirs conform to the general idea within the U.S. strategic community that China is a rising military threat. Gates notes, in a recounting of the 2010 Shangri-La Dialogue, that a retired PLA general told him the reason China would no longer accept U.S. arms sales to Taiwan: “now we are strong.” Gates paints a picture of China as a rising military power that will now throw its weight around to correct historical “mistakes” (from U.S. arms sales to Taiwan to territorial disputes) left over from China’s previous weakness. As a result, Gates believes that “a robust American air and naval presence in the Pacific” (in other words, the “pivot to Asia”) is the best way to ensure peace in the region.

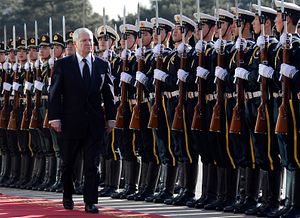

In response to a growing concern over Chinese motives, both President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama placed an emphasis on improving the military-to-military relationship with Beijing. Gates notes that by 2007, then-Presidents George W. Bush and Hu Jintao had agreed that the U.S.-China military-to-military relationship needed more work. This focus continued under Obama — in a 2009 meeting with General Xu Caihou, Vice Chairman of China’s Central Military Commission, Gates urged an end to the “on-again, off-again” nature of mil-to-mil relations.

Gates notes in his memoirs that he wanted a military relationship that would be “largely immune to political differences” — in other words, one that would not be derailed by political moves such as U.S. arms sales to Taiwan. The ideal relationship, according to Gates, would also allow for dialogue “on sensitive subjects like nuclear strategy as well as contingency planning on North Korea.” Using the example of U.S. talks with the Soviet Union, Gates put forth his belief that “dialogue had helped prevent misunderstandings and miscalculations.”

Despite apparent buy-in from Beijing, Gates believes that PLA leaders were not on board with the vision. “It was clear,” Gates writes, “that Chinese military leaders were leery of a real dialogue.” Bloomberg quotes Gates as saying that Hu Jintao “did not have strong control” of the People’s Liberation Army, a perception that is widely shared by many China experts. Because of this, Gates blames the lack of progress on mil-to-mil relations on the PLA, not on Hu.

For example, Gates notes that, despite an agreement between Bush and Hu to “pursue bilateral discussions of nuclear strategy … it was pretty plain that the People’s Liberation Army hadn’t received the memo.” Gates also concluded that various provocative actions taken in 2009 and 2010 (from the USS Impeccable being “aggressively harassed by Chinese boats in the South China Sea” to the Chinese military testing a stealth fighter while Gates was in Beijing on a formal visit) had been done “without the knowledge of the civilian leadership in Beijing.” In fact, Gates posits that Chinese military leaders were reluctant to agree to a formal military dialogue in part because Chinese civilian officials would be in attendance — the military leaders did not want civilian leaders involved in decision making. On one hand, the idea of the PLA becoming more independent is worrisome to Gates. However, this narrative also allows Chinese leaders and U.S. strategists (including Gates) to effectively write-off concerning moves. It’s far less damaging to relations for U.S. policymakers to believe that controversial moves are the act of a rogue general rather than orders from the top Chinese leadership.

In the Bloomberg article, Gates notes that this excuse is no longer valid, as Xi Jinping has moved quickly to consolidate his control over the military. Now when China’s military makes a move, such as announcing the ADIZ, Gates says, “you’ve got to assume President Xi approved that and is on board.” Gates seems convinced that, during Hu’s tenure, the military was acting largely on its own. Now, with Xi firmly in control, it’s more apparent that provocative moves are approved by top leadership, and thus part of China’s long-term strategy.

Gates makes no attempt to hide that China is viewed as one of the major military threats to the United States. Towards the end of his book, Gates notes his concerns with China’s growing military capabilities, which he believes are “designed to keep U.S. air and naval assets well east of the South China Sea and Taiwan.” In turn, when deciding which U.S. military programs to cut, Gates analyzed projects from the F-22 to the missile defense program based on their potential utility in the event of a conflict with China. It’s generally assumed that current U.S. military technology is designed with an eye towards China, but it’s still fairly rare for DoD personnel to be so candid about it. (It’s also interesting to note that Gates acknowledges the U.S. has a horrible track record “in predicting where we will be militarily engaged next,” so perhaps we should take talk of a “China threat” with a grain of salt.)

Despite his differences with Obama, Gates seems to have had no major qualms about his China policy. Gates notes China as one of the issues where “the president, vice president, [then-Secretary of State Hillary] Clinton, [former National Security Advisor James] Jones, [then-National Security Advisor Tom] Donilon, and I were usually on the same page.” I would imagine this is disappointing (but not surprising) for Chinese leaders. The Chinese are clearly not happy with what they see as U.S. “Cold War thinking” and attempts at containment. However, given the level of consensus Gates describes, don’t expect the United States’ policy to change anytime soon.