I recently visited the Smithsonian Museum’s Sackler Gallery’s new exhibition, Nasta‘liq: The Genius of Persian Calligraphy in Washington, D.C. The Sackler Gallery frequently features new and never-before-seen exhibitions devoted to themes in Asian and Middle Eastern art and culture.

According to the exhibition’s website, “Nasta‛liq: The Genius of Persian Calligraphy is the first exhibition of its kind to focus on nasta‛liq, a calligraphic script that developed in the fourteenth century in Iran and remains one of the most expressive forms of aesthetic refinement in Persian culture to this day.”

Understanding nasta‘liq’s history and development sheds light on the often forgotten but not too distant period of the non-Arab, Persianate world that stretched from Istanbul to Delhi. This culture is not synonymous with modern Iranian culture and represented a cosmopolitan, elite culture. Additionally, this world, while Islamic in religion, was not synonymous with the Islamic or Arab world. Not all art produced in the Islamic world deserves to be lumped together as Islamic art in the same way that not all works produced by artists who happened to be Christian form a single, natural category known as “Christian Art.” The individual calligraphers have distinct personalities and styles as varied as those of Western artists from a contemporary period, the Renaissance.

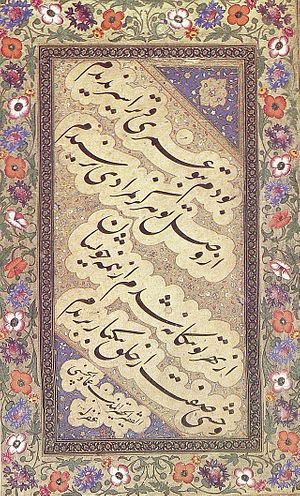

The vast majority of nasta‘liq calligraphy is not in fact, of a religious nature, though individual works may contain mystical elements. As a panel in the exhibition points out, nasta‘liq was primarily designed to write Persian poetry and subsequently spread to languages influenced by the Persian literary tradition: Ottoman Turkish, Urdu, and Chagatai (the pre-modern Turkic literary language of Central Asia). Today, nasta‘liq is probably most closely associated with Urdu. Modern Urdu is primarily written in the highly sinuous nasta‘liq script, which apparently caught on strongly in the Mughal Empire. On the other hand, in modern Persian/Dari, the script is used mostly for decorative or poetic purposes. Quite a lot of folios displaying poetry verses utilizing the script in the exhibit were from Mughal collections, suggesting that the Mughals had absorbed the Indian love for the ornate in the arts.

The Mughals liked to select a few choice verses of poetry, and have them inscribed in nasta‘liq before mounting them on panels. Nasta‘liq, which is the most fluid variation of the Arabic alphabet, thus became as important as the content of its text itself due to its visual essence. We learn from the exhibit that according to tradition, the script was invented by Mir Ali Tabrizi (flourished between 1370-1410 C.E.), from Tabriz, in modern day Iran. Tabrizi, according to legend, created the script after receiving a dream from Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad that instructed him “to draw letters that look like the wings of flying geese.”

Certainly Tabrizi and his successors took this directive to heart. The art of nasta‘liq reached its mature form in the eastern Persian city of Herat (in today’s western Afghanistan) where two other artists whose calligraphy was displayed in the exhibit, Sultan Ali Mashhadi and Mir Ali Haravi, worked. The exhibit concludes with the art of Mir Imad al-Hasani (died in 1615), from Qazvin, Iran, who is generally considered the master of nasta‘liq. He may have been murdered due to the jealously of other calligraphers. His works were avidly collected by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, who also built the Taj Mahal.

The best way to describe the effect of being in a room filled with nasta‘liq calligraphy is to imagine the words becoming animated and leaping out at you. The exhibit immerses one in a world that is very distant from our own modern world in many ways. It is undoubtedly harder to present an exhibit on (or write about) non-Western cultures for a primarily Western audience because the very intellectual bases or premises of their arts might be unfamiliar to a general Western audience, but the Sackler Gallery does a good job at conveying ideas across cultures and time.

While not all Diplomat readers will be able to visit the exhibit or other similar exhibits, I encourage them to delve into the history, culture, and art of other civilizations in order to empathize with and understand these cultures from their own point of view rather than forming impressions purely on the basis of current events and politics. Realpolitik, in fact, only becomes meaningful when it is approached through the lens of understanding where other people and nations are coming from.