Following the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) unanimous ruling undermining the legal basis for China’s “nine-dash line” claim, Beijing repeated its prior threat to establish an aircraft defense identification zone (ADIZ) above the South China Sea (SCS). An ADIZ is an area of airspace, adjacent to but beyond the national airspace and territory of the state, where aircraft are identified, monitored, and controlled in the interest of national security.

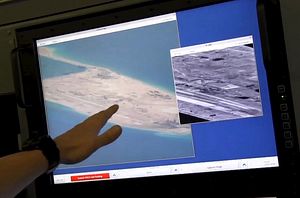

Presumably the purpose of a South China Sea ADIZ would be to reinforce China’s territorial claims – a tangible rejoinder to the PCA’s award and international criticism. In November 2014, Beijing established an ADIZ over the East China Sea (“ECS ADIZ”) encompassing disputed maritime territory. The ADIZ could also serve as a means of excluding and deterring U.S. freedom of navigation operations, which include military flights designed to challenge excessive claims to maritime jurisdiction. China has developed a series of landing strips on reclaimed land in the contested Spratly archipelago that could be used to enforce the ADIZ.

However, a Chinese ADIZ above the South China Sea, in addition to aggravating tensions, would be misguided as a matter of international law and mistaken as a matter of policy. ADIZs are creatures of customary international law, the implementation of which are conditioned by principles derived from the inherent right of self-defense and treaties such as the Convention on International Civil Aviation (Chicago Convention) and United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Although more than 20 states, including the United States, have established ADIZs, these limited defensive zones have not been used for the greater lawfare ends potentially envisioned by Beijing. An examination of the fundamental elements of ADIZs, reveals the folly of such an approach.

First, the role of ADIZs is to provide a means of anticipatory self-defense from incoming and immediate threats emanating above the high seas. The ADIZ is a modern variant and extension of the “cannon-shot” rule, which provided for a buffer zone in coastal waters based on the reach of littoral defenses. During the Cold War, the United States established the first ADIZs as a means of protecting the homeland from the inbound threat posed by long-range Soviet bombers. Employing an ADIZ to aggrandize disputed maritime claims would deviate from state practice and encroach upon the rights of all states in the high seas. In this scenario, the legal rationale of ADIZs would be essentially reversed from defensive to offensive, from the protection of national sovereignty to the coercive extension of sovereignty.

Second, ADIZs can only be legally applied in relation to preventing the unauthorized entry of aircraft into the national airspace. ADIZs cannot be used to control foreign aircraft not intending to enter the national airspace. States only enjoy exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above their territory, a right which ends at the 12 nautical mile border of the territorial sea. Beyond this territorial belt, all states enjoy the high seas freedoms, including freedom of overflight, a customary principle memorialized in UNCLOS. These limitations may frustrate Beijing’s broad design. For example, even if China ignores the PCA’s ruling and could validly claim that Fiery Cross Reef, site of large-scale Chinese reclamation activities, is an “island” entitled to a territorial sea, Beijing could not prevent U.S. military aircraft from traversing the adjacent international airspace.

Third, establishment of an ADIZ must follow standard notice and coordination procedures. The Chicago Convention mandates timely and structured cooperation prior to establishing security zones in order to mitigate risks to civil aviation such as hazardous aircraft interceptions. In addition, the procedures used to identify, locate, and control aircraft in ADIZs are similar to those used by states assigned authority, under the Chicago Convention, for providing air traffic services in international airspace. For instance, the Philippines is responsible for providing air traffic services within the Manila Flight Information Region (FIR), an area that includes large swaths of airspace in the South China Sea. In the case of the ECS ADIZ, Beijing unilaterally established the zone without engaging or communicating with stakeholders in the region through established channels. Similarly, since a South China Sea ADIZ would be a rebuke to competing claimants, it is doubtful that China would seek prior input from or collaborate with neighboring states like the Philippines. A Chinese ADIZ that overlaps with existing air traffic regions in the South China Sea could lead to surprise, miscalculation, and the threat of force against commercial carriers. Beijing would be correctly blamed for any resulting catastrophe.

Fourth, states purport to apply ADIZs to both civil and state aircraft, an often problematic distinction under international law. Following the Korean Airlines Flight 007 incident in which a Soviet fighter jet shot down a scheduled commercial aircraft, killing all 269 persons on board, the Chicago Convention was amended to expressly prohibit the use of weapons against civil aircraft in flight. However, identifying whether a particular flight qualifies as one by “state aircraft” or “civil aircraft” is subject to interpretation and inconsistently applied. This uncertainty has led to controversy regarding whether the Chicago Convention’s protective cover applies to specific flights in international airspace. Following the establishment of the ECS ADIZ, China sought to reassure commercial airlines that normal flights would not be disrupted even though the official rules published by Beijing allowed for this scenario. Unsurprisingly, however, when China turned back Lao Airlines Flight QV916 on July 25, 2015, initial reports mistakenly concluded that Beijing had enforced the ECS ADIZ. A South China Sea ADIZ would only increase the risk of confusion and miscommunication, thereby inhibiting one of the world’s great transit lanes.

Fifth, states enforce ADIZs through military interception, which ultimately may lead to the threat or application of force against non-compliant aircraft. In September 2015, the United States and China concluded Annex III to the Memorandum of Understanding On the Rules of Behavior for the Safety of Air and Maritime Encounters. The parties agreed to actions and maneuvers to prevent collisions between U.S. and Chinese military aircraft, including interception procedures. This document, however, is neither legally binding nor applicable to third parties. A state’s legal ability to use force against intrusions of sovereign territorial airspace is much broader than the right to self-defense in international airspace. How would China view ADIZ enforcement in the South China Sea? In the ECS ADIZ, Chinese interceptor aircraft have breached international norms, endangering safety by reportedly coming within 200 feet of Japanese military reconnaissance aircraft. Needless to say, an accident or incident involving a Chinese military interception would contravene commitments of self-restraint and the peaceful resolution of disputes, as set forth in the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct (DOC) of Parties in the South China Sea.

Sixth, although ADIZs have extensive temporal and geographic range, international law establishes important parameters on their scope. For instance, the Contiguous U.S. ADIZ extends more than 400 miles into the Pacific Ocean and has been in place for more than fifty years. However, even U.S. ADIZs must not unduly interfere with high seas freedoms or exceed the functional jurisdiction associated with maritime zones under UNCLOS. With regard to an economic exclusive zone (EEZ), the coastal state has “sovereign rights” for the purpose of exploiting and managing natural resources, but an EEZ does not generate new security rights, including in relation to the international airspace above. Nevertheless, during the E-P3 incident of April 1, 2001, in which a Chinese fighter collided with a U.S. reconnaissance aircraft flying above China’s EEZ, Beijing attempted to link novel security rights with UNCLOS maritime zones.

Importantly, the scope of an ADIZ must be measured by principles of self-defense: Is the area covered and the indefinite duration of the zone necessary and proportional to the actual threat presented? As Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin recently acknowledged, an ADIZ depends on the threat. In the Nicaragua case, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) held that U.S. naval maneuvers in the immediate vicinity, but beyond Nicaragua’s territorial sea did not constitute a prohibited threat or use of force. Extending this logic, U.S. freedom of navigation operations above the international waters of the South China Sea would not serve as a credible basis for enforcing a Chinese ADIZ.

Even if China were to use an ADIZ for a sui generis prescriptive purpose, there is the significant problem of configuring the zone to align with Beijing’s broad, yet inconsistent claims. Would the ADIZ surround the nine-dash line, thereby encompassing the entirety of the South China Sea, or would the zone merely safeguard various Chinese-claimed islands and features, a slight but definitive concession? The ECS ADIZ roughly corresponds with China’s EEZ and covers the disputed Senkaku Islands, but what value – legal, tactical or otherwise – has this measure brought to China? According to a U.S. Congressional report, the ECS ADIZ is more bluster than actual buffer. Unlike aggressive, but temporary military exercises, an ADIZ would be a near-permanent policy prescription in the South China Sea. Any strategic gain from Chinese ambiguity would be lost, the diplomatic off-ramps narrowed and the ill-conceived nature of the policy revealed. An ADIZ would become another spurious boundary to defend in the turbulent South China Sea.

Roncevert Ganan Almond is a partner at The Wicks Group, based in Washington, D.C. He has advised the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission on issues concerning international law and written extensively on maritime disputes in the Asia-Pacific. The views expressed here are strictly his own.