Unsurprisingly, Indian leaders were absent from the Second Belt and Road Forum (BRF) for International Cooperation hosted by China in Beijing on April 26 and 27. New Delhi has been a vocal opponent of its neighbor China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a multi-billion dollar overseas infrastructure investment initiative spearheaded by Chinese President Xi Jinping.

India also boycotted the first BRF in 2017, citing its concern over the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project, China’s flagship BRI project in Pakistan. India cited issues of “sovereignty” and “territorial integrity” as the roots of its concerns. The CPEC project passes through Indian-claimed but Pakistan-administered portions of Kashmir.

China has reiterated that the Indian absence from the BRI festivities will not impact the Indo-China relationship. At a press conference about the BRF, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated that the ties between India and China were insulated from differences due to BRI, as reported by The Hindu.

Trying to assuage Indian fears around CPEC, Wang has argued, “One of our differences is how (we) look at the BRI. The Indian side has its concerns. We understand that and that is why we have stated clearly on many occasions that the BRI including the CPEC is only an economic initiative and it does not target any third country and has nothing to do with the sovereign and territorial disputes left from history between any two countries.”

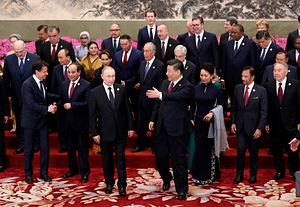

Thirty-seven heads of state, numerous ministers and 5,000 delegates participated in the second BRF. India was not the only South Asian country who turned down China’s invitation. Pakistan and Nepal were the only two South Asian nations that sent their heads of state and government to the BRF.

Nevertheless, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal and Pakistan have all allowed new BRI projects in their countries. Not only is South Asia one of the fastest growing regions in Asia, it is also vital to China’s goal of building a “String of Pearls” in the Indian Ocean.

CPEC and its Effect on India-Pakistan-China Relations

The importance of Pakistan, China’s “all weather ally,” to BRI cannot be understated. Of the $90 billion invested by China so far in BRI, around one-third, $27 billion, has been invested in Pakistan. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan was one of the seven leaders who addressed the summit.

CPEC passes through Pakistan-administered Kashmir, leaving India no choice but to boycott the BRI or face serious complications in future territorial claims vis-a-vis Pakistan and China, which claims India’s Arunachal Pradesh.

China’s claim to Arunachal Pradesh is also a major cause of concern for India. Less than two months after India’s initial boycott of BRI, the two neighbors were involved in a 72-day standoff in the Doklam plateau bordering India, China and Bhutan.

Furthermore, given China’s resistance for the past decade to designate Pakistan-based Masood Azhar, the Jaish-e Mohammad (JeM) chief allegedly responsible for the recent Pulwama blasts in India, on the UN Security Council’s terrorism list, makes Delhi rightfully wary of the deepening ties between its two nuclear-armed neighbors.

Last week, China reversed its stance on Azhar, after rejecting the last four similar bids in the past decade. Azhar has been added to the UNSC’s 1267 sanctions list in what is being touted as a major diplomatic victory for Modi’s foreign policy. Some claim that the blacklisting has come at the cost of Indian silence on the BRI.

The Case of the Missing BCIM

Noticeably, the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor was absent from China’s list of BRI projects. The BCIM, originally proposed in early 1990s, would connect China’s Kunming with Kolkata through Dhaka in Bangladesh and Mandalay in Myanmar.

It was moved to Track I in 2013. However, despite the positive rhetoric, little progress has been made since on the BCIM after it was initially listed as one of the six main land corridors of BRI.

It is largely believed that BCIM has become a victim to India-China BRI politics and the heightened mistrust between the neighbors after the 2017 Dokhlam standoff.

Indian Response to the BRI

Alongside Japan and the United States, India has been highly critical of BRI as “debt-trap diplomacy,” particularly after Sri Lanka handed over a deep-sea port to China for 99 years after being unable to pay its loans back.

Following global criticism, Xi has tried to reassure the international community through a joint communique with 37 heads of state, pledging to pursue “high standard, people-centered and sustainable development” that is “in line with our national legislation, regulatory frameworks, international obligations, applicable international norms and standards.”

Furthermore, India has recently set up an Indo-Pacific division in its Ministry of External Affairs. The Act East Policy has been a hallmark of Modi’s foreign policy, if not in action, then at least in rhetoric. The new division puts the Indian Ocean at the center of India’s Indo-Pacific strategy. This conceptualization serves to counteract the broader geopolitical effects that China’s Maritime Silk Road would have on the Indian Ocean region.

China is far better equipped for natural resource and infrastructure diplomacy than India. India has tried to counter this by joining other regional actors like Japan and the United States in forming alternative infrastructure corridors. For instance, along with Japan, India has proposed the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC). The AAGC is a sea corridor that will connect Africa with India, Southeast Asia and Oceania.

Despite the rocky aspects of their relationship, India and China continue to cooperation in some areas, such as Chinese projects in India. Since 2014, Chinese investments in India have increased rapidly, with almost 80 percent of $8 billion in Chinese funding falling within this period, according to an article in the SCMP.

Bansari Kamdar is a freelance journalist and researcher presently based in Boston, MA. She specializes in South Asian political economy and security issues.