In China’s political philosophy, rural is half the China state: half the polity is urban, the other half rural. While state-party dichotomies tend to dominate analyses of China’s elite politics, the rural aspect of the urban-rural split is often overlooked. More than simply agricultural, peasant, or village policy, rural affairs is a broad portfolio. Yet while this rural affairs portfolio is a sprawl of governance, economic, and social policy competence, there is no Politburo chair institutionalized for rural affairs responsibility.

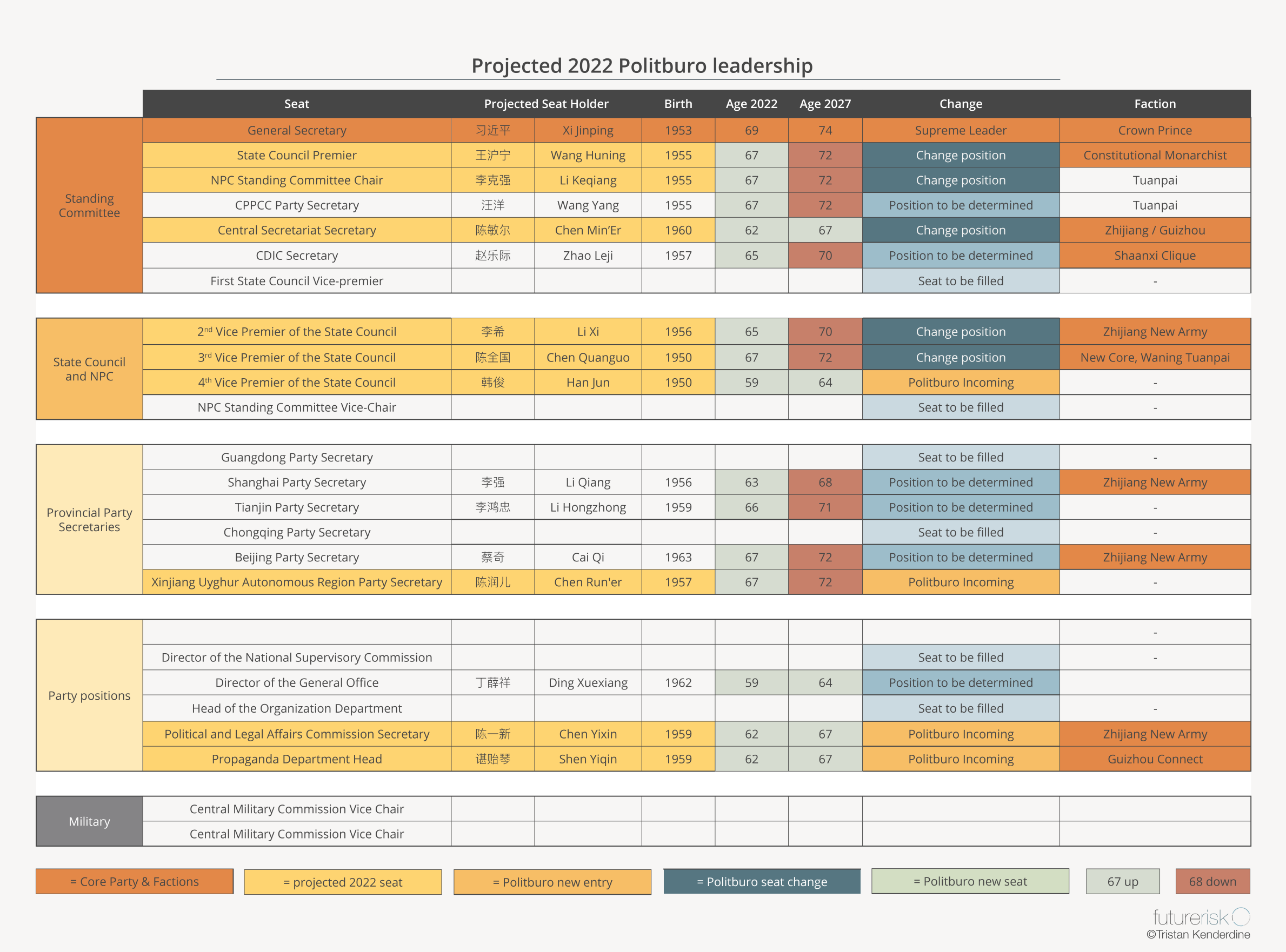

Rural affairs is largely governed from within the State Council, although outside input comes from the National People’s Congress Agriculture and Rural Affairs Committee, the CPPCC Agriculture and Rural Affairs Committee, and the Party Central Leading Group for Rural Work, the office for which sits in the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. This ministry also coordinates much of China’s foreign agricultural policy and runs adjacent to resources and environment policy. Within the Politburo framework above these state structures, rural affairs is usually overseen by State Council vice premiers.

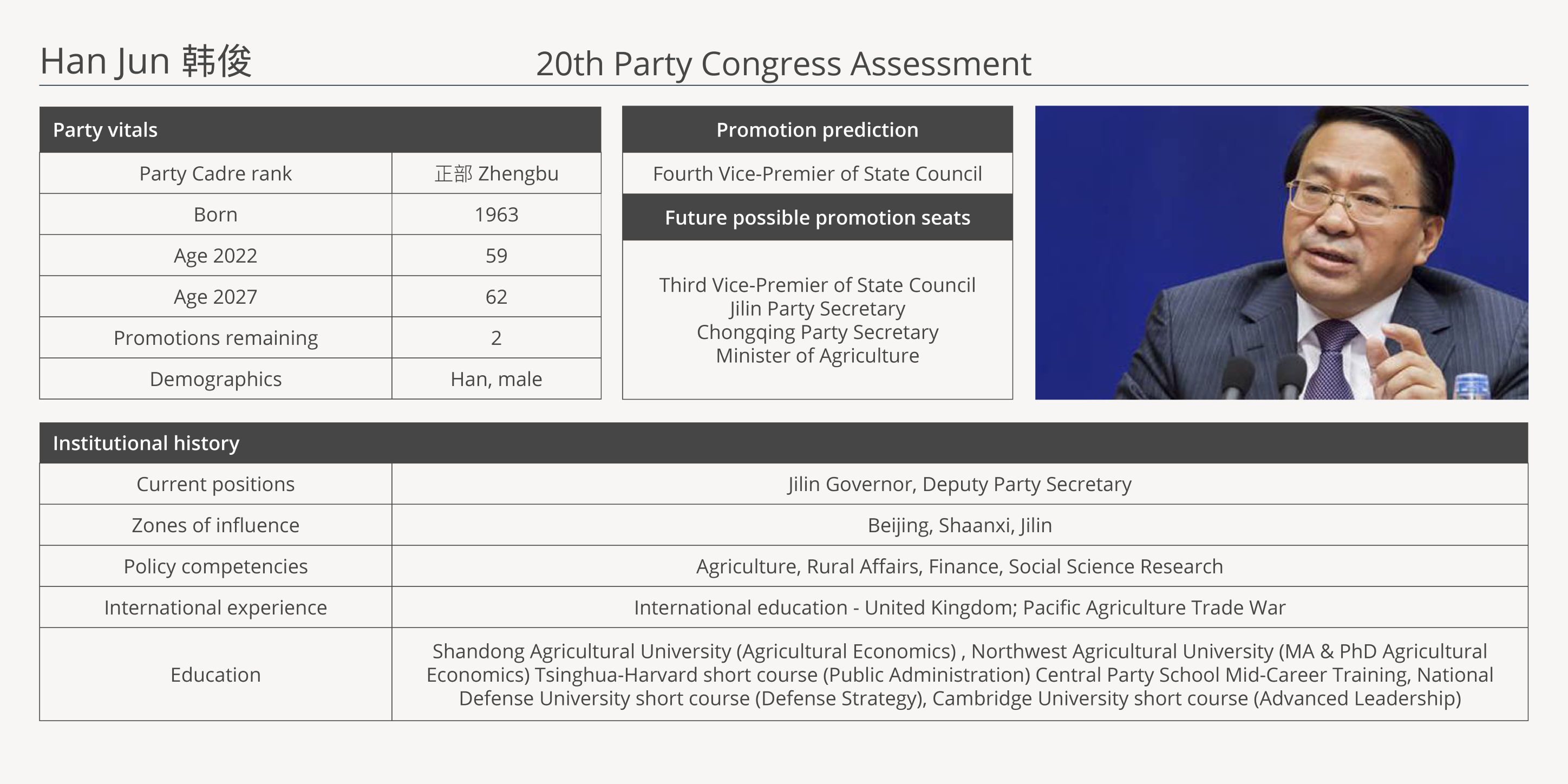

Han Jun, the governor and deputy party secretary of Jilin province, is now in prime position to ascend to become one of the four State Council vice premiers in the 2022 Politburo. While rural, land, resources, and agriculture policy is currently split between Han Zheng and Hu Chunhua, Han Jun is the genuine rural affairs policy specialist in the current administration. Politically, Han is a policy pragmatist and technocrat in the style of Wang Yang or Zhang Gaoli. Han served previously on the Central Leading Group for Finance and Economics from 2014-2020, a period that saw the ouster of many right-liberal, market-minded financial cadres, the end of the careers of Lou Jiwei and Zhou Xiaochuan, and the movement back toward centralized control of financial markets. Han is thus well placed as a generalist, with experience in rural policy research, and practical policy implementation in finance, economics, rural affairs, and agriculture.

Unlike the cadre cohort before him, with their disrupted educations during the Cultural Revolution, Han stayed entirely within the higher education system from bachelor to terminal degree, emerging aged 26 with a doctorate in agricultural economics. He then went straight in to policy research, moving from Shaanxi to Beijing to take up his first job at the Rural Development Research Center. After nine months of fieldwork in poverty alleviation back in Shaanxi, Han returned to Beijing and spent a decade at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, rising to deputy director of the Institute of Rural Development. In 2001 Han then moved to the rural economics section of the State Council’s Development Research Center where, by 2010, he had again risen to deputy director.

Through this decade at the Development Research Center, Han took the full-length one year Central Party School training in 2006 and a Tsinghua-Harvard short course on public administration in 2003. In September 2012 Han also took a three-week Cambridge Judge Business School executive training course, immediately after he had attended the three-month National Defense Strategy Research course of the PLA’s National Defense University. This national strategic defense training of provincial level cadres has intensified in recent years, with a focus on network and supply-chain security in food, water, energy, electricity, and transport.

2014 was Han’s big break, as he was made deputy director of the Office of the Central Leading Group for Rural Work and also deputy director of the Office of the Central Leading Group for Finance and Economics. This put him in a unique position. Rural development and rural finance is always an important policy position, but as concurrent deputy director of the finance and economics working group Han was directly among the leadership of the entire Chinese economy, with policy purview over all facets of financing China’s economy and wider economic policy.

Han had been missing executive leadership experience, but in January 2021 he was made governor and deputy party secretary for Jilin, working under Party Secretary Jing Junhai. Jilin, located on the Songhua River on the Manchurian Plain, is an important northeastern agricultural production center for China, a major producer of rice, soybean, maize, and sorghum.

Han Jun moving to Jilin governor as a prelude to returning to a central position would be a similar trajectory to Han Changfu, who was first governor of Jilin before becoming minister of agriculture. Until 2020 Han Changfu had governed with policy competence over China’s rise into global food markets, both through global commodity markets as well as the Belt and Road agriculture plans to develop a series of offshore production bases.

Given his inexperience in other policy fields and lack of leadership experience, it would be fair to consider Han staying as Jilin governor through the 2022-2027 term or at most to be promoted to a non-Politburo provincial party secretary position. However, given the ongoing rectification purge, Han looks like he is being rapidly promoted. Han could conceivably go to one of the Politburo provincial party secretary positions, but his lack of leadership or party position experience mean he is more likely being elevated to provincial governor now as a preparatory step before going to one of the four State Council vice premier positions.

Given his inexperience in other policy fields and lack of leadership experience, it would be fair to consider Han staying as Jilin governor through the 2022-2027 term or at most to be promoted to a non-Politburo provincial party secretary position. However, given the ongoing rectification purge, Han looks like he is being rapidly promoted. Han could conceivably go to one of the Politburo provincial party secretary positions, but his lack of leadership or party position experience mean he is more likely being elevated to provincial governor now as a preparatory step before going to one of the four State Council vice premier positions.

Policy-wise, for a third Xi administration depending on poverty alleviation and rural development for legitimacy, there has been a dearth of rural policy since 2018. This has left poverty alleviation as the only rural policy and governance narrative. Han Jun would thus be handed a portfolio of policy problems and few tools with which to solve them.

Han’s rural affairs research career has focused acutely on rural finance, hukou reform, and land reform. These three big policy challenges of contemporary China are persistent insoluble problems, and they will remain acutely problematic through the 2020s. As China seems destined for a decade of neo-Maoist economic policy, concerns over grain shortages and food security are already high on the national security agenda, requiring an adept technocrat to manage both domestic and foreign policy responses.

As State Council rural affairs specialist, Han would assume control of an informal policy portfolio centered on rural, agricultural, finance, and food security affairs, manifested in various leading groups and party policy positions. His age means he qualifies for the next two Central Committees, meaning if he does not make Politburo this term, he almost certainly would in 2027. Being in the same age cohort as Hu Chunhua and Chen Min’er, though, opens space for Han to become a centrist state buffer between Xi’s CCP core and any right-liberal resurgence. Expect Han’s State Council vice premier policy portfolio to be explicitly centered on poverty alleviation, but implicitly centered on the institutional transition of China’s coastal model to the inland, while simultaneously managing the food security aspects of any future trade war activity.