Japanese soft power and political clout has always been underestimated, with its economic largesse, alliance with Washington, and influence among Western countries forming a backbone in Asian regional diplomacy that can be put to good use when needed.

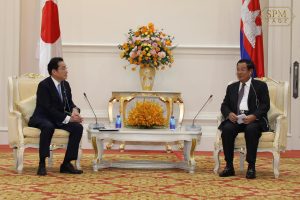

Against that backdrop – and with much pomp – recently elected Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio arrived in Phnom Penh on Sunday for a two day visit and gifted his Cambodian counterpart Hun Sen with a glad bag of political tidings.

Hun Sen asked Kishida to consider a free trade agreement, import more Cambodian agricultural products, and encourage Japanese companies – including Panasonic, Toshiba, Mitsubishi, and Yamaha – to set up factories here.

The Cambodian leader also asked Japan to accept more Cambodian skilled workers and trainees on a continuous basis once restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic have eased.

These were modest requests for a country in need of investment alternatives from China and whose economy, like elsewhere, has been brutalized by the pandemic. Phnom Penh also needs to improve its standing with Washington, which Kishida furnished.

That included a Japanese nod in favor of Hun Sen’s troubled attempts at negotiating with the junta in Myanmar as ASEAN special envoy and Cambodian Foreign Minister Prak Sokhonn left for his first visit there on Monday, as Kishida flew home.

Importantly, the two leaders agreed to elevate their bilateral strategic partnership to a “new level” and made a series of security plays that should bolster Hun Sen as chair of ASEAN and pave a better way forward in his relationships with the West.

Despite Cambodia’s long standing friendship with Pyongyang, Hun Sen alongside Kishida expressed “grave concerns over the continued ballistic missile” launches by North Korea and then tweaked Beijing’s beak by “committing to a sustainable Mekong River.”

The Mekong, suffering a four year drought amid an outcry over Chinese dam construction, is considered by many analysts as the number two regional security threat after the South China Sea and is a constant problem in domestic politics. In a clear reference to China, Japan and Cambodia urged “countries concerned to avoid unilateral actions that would increase tensions or complicate the situation in the South China Sea.”

A joint statement, which did not mention Russia by name, called for “an immediate stop of the use of force and the withdrawal of the military forces from the territory of Ukraine” – a further signal in Cambodia’s shifting foreign policy, given its traditional ties with Moscow.

They also underscored “that any armed attack on and threat against nuclear facilities devoted to peaceful purposes constitutes a violation of international law” – a clear reference to Russian attacks on the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant.

Japan, in a break from the past, was among the first countries to raise its voice and sanction Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. Kishida made it well known ahead of his departure for India and then Cambodia that that was the point of his trip.

Hun Sen hit the desired notes where Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi demurred, which was not a good look for a country that sits inside the Quad with Japan, Australia, and the United States in a partnership designed to curtail Chinese belligerence, particularly on the high seas.

Therein lies Hun Sen’s pressure point. In return for investment dollars, Phnom Penh has acted as Beijing’s proxy over issues such as the South China Sea and its model for a code of conduct, which has divided ASEAN.

Chinese development of a 30 kilometer stretch of coastline, including a deep-water port at Sihanoukville, eight-lane highways encircling an international airport, and, in particular, the development of the Ream Naval Base for Chinese use has annoyed the United States.

But the heady days of massive Chinese development are over and the coast is littered with derelict casinos, half-built skyscrapers, empty apartment blocks. Hun Sen is in dire need of alternatives.

In a move that will be watched closely in Washington, Hun Sen and Kishida said they will fully cooperate on developing the port at Sihanoukville as a hub for the Mekong region and beyond with continuous visits now expected there and at Ream by the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force.

Whether these political maneuverings, with Japan’s support, will lift Cambodia’s standing in the West remains to be seen because there were controversial issues left out of the public arena.

Hun Sen is facing stinging criticisms over the deterioration of democratic standards at home and eyebrows have been raised over his decision to stand down after next year’s election and simply hand power to his eldest son Hun Manet.

Hun Manet visited Japan last month in what was widely seen as shoring up his own political future while prepping for Kishida’s meet with his father last weekend.

According to the Cambodian semi-official outlet Fresh News, Japanese Foreign Ministe

Therein lies the rub.