Maritime disputes in the Indo-Pacific frequently draw headlines. The disputes in the South China Sea, with its strategically important shipping lanes and natural gas reserves, have attracted the most attention – not least because of frequent altercations, such as a recent spat between the Chinese and Filipino coast guards involving a laser weapon. Meanwhile, in the East China Sea, tensions between Beijing and Tokyo over islands administered by Japan as the Senkaku Islands but claimed by China as the Diaoyu Islands, continue to impact bilateral relations.

Now, a new potential conflict further north risks stoking tensions between the three East Asian economic powerhouses of China, Japan, and South Korea in the area known as the Joint Development Zone (JDZ).

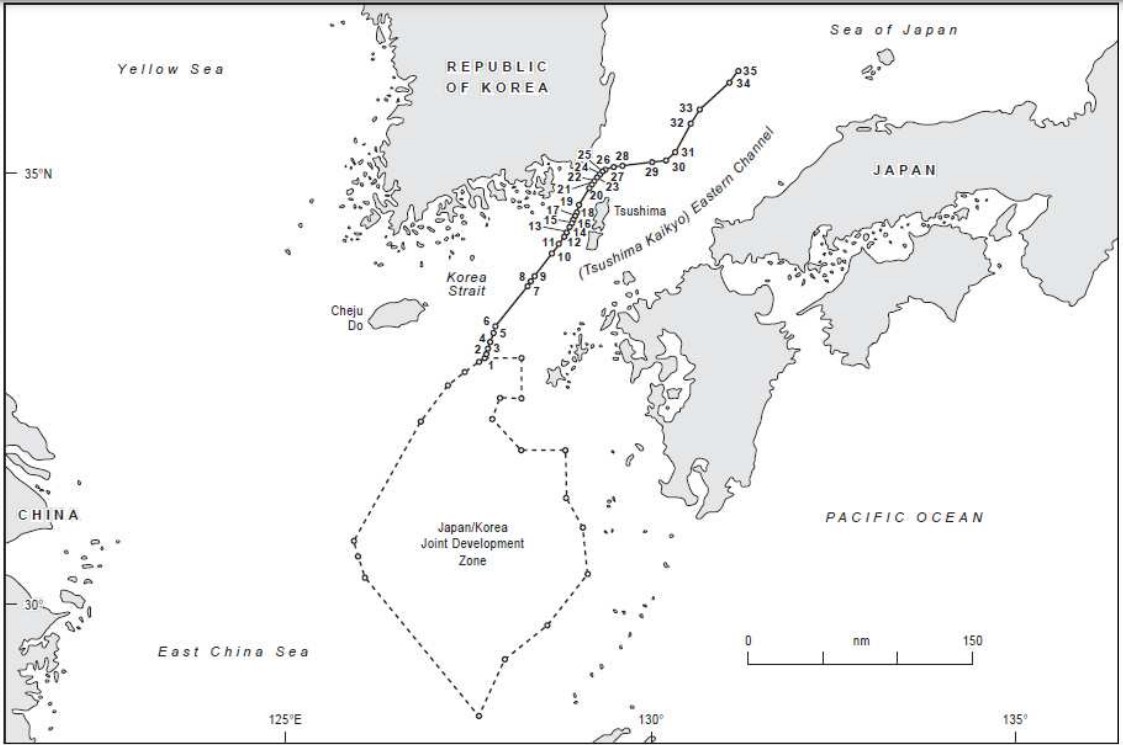

The JDZ’s origins date back to a 1974 treaty, when Japan and South Korea agreed to designate the zone as a shared area for petroleum and natural gas exploration. This agreement came after a report by the U.N. Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (today the U.N. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific) claimed that the maritime area in between the two countries could potentially carry reserves of petroleum and natural gas comparable with those in the Persian Gulf.

The Korean government laid claim to the area based on the principle of “natural prolongation of the land territory or domain or land sovereignty of the coastal state” based on an International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling in 1969. Japan based its claim on the median line principle devised in 1958 “in the absence of agreement” or “special circumstances.” Although Seoul and Tokyo relied on separate interpretations of maritime law, they came to an agreement in 1974 to jointly develop their overlapping continental shelf in search of petroleum and natural gas.

Map from the United Nations.

However, since 2010 Japan has not made any efforts to engage in joint exploration or development. Assessments from Seoul and Tokyo differ starkly in estimates of the commercially significant oil reserves, and Japan has cited this as the reason behind its refusal to engage in any more exploration. Researchers from South Korea claim that there are in fact substantial reserves in the area, citing advancements in exploration technology and the presence of deposits successfully extracted by China nearby in the same geological structure.

Some in South Korea accuse Tokyo of waiting until the JDZ expires, which is set to happen in five years, in order to seize the area for itself. Indeed, with the adoption in 1982 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the principle of “natural prolongation of land territory/sovereignty of the coastal state” that South Korea previously relied on has reduced in significance, weakening Seoul’s claim to the area.

Under the administrations of South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, both governments have carefully navigated low domestic approval ratings to slowly approach reconciliation over historical grievances, particularly regarding the 2018 ruling by a South Korean court that Japanese companies must compensate victims of wartime forced labor. However, tensions between the two countries over territorial issues have persisted in the East Sea/Sea of Japan, where the South Korean-administered island of Dokdo is also claimed by Tokyo.

If the JDZ expires and Japan does move to unilaterally claim the natural resources in the area, this would pose several challenges for Northeast Asian security.

First, beyond the potential of untapped hydrocarbons, the JDZ is also a crucial area for maritime access, particularly for South Korea. Unlike the Japanese archipelago and the Chinese mainland, the Korean Peninsula does not extend far out into the Pacific, and its access to the broader ocean is partially limited by its two neighbors. If Tokyo decides to occupy the JDZ following its expiration, Seoul’s access to global trade and naval power projection capabilities will be significantly hampered. As a nation heavily reliant on trade, this is a crucial security risk for South Korea.

Second, it remains to be seen how Beijing would react to the potential dissolution of the JDZ. China already has overlapping EEZs with both South Korea and Japan, and it is likely to make stronger claims to the region in the future. Beijing and Tokyo could in theory enter bilateral agreements to divide the JDZ into two larger zones; the exclusion of South Korea would provide China with an opportunity to drive a wedge into the trilateral security cooperation between South Korea, Japan, and the United States.

Although there are occasional disputes reported in the media, Chinese activity in the Yellow Sea between itself and the Korean Peninsula has been relatively muted in comparison to its assertiveness in the East and South China Seas. Beijing instead prefers to diplomatically engage with Seoul to resolve disputes. If China were to provide South Korea with a minor concession in the JDZ area, it would draw Seoul closer to Beijing away from Tokyo, and consequently Washington.

Amid a slow but steady thaw in Japan-South Korea relations, Tokyo faces a choice. Will the Japanese government respond to South Korean calls for joint exploration and a treaty renewal? Or will Japan instead seek to consolidate its hold over a crucial maritime area and any potential resources therein? The impact of this decision will not only affect the future of the Seoul-Tokyo relationship, but also the strategic initiatives of Washington and Beijing as well.