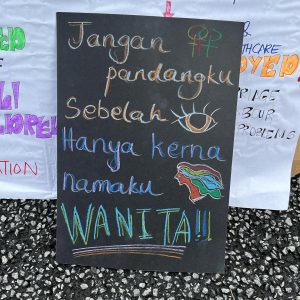

On March 12, activists across Malaysia converged on the capital of Kuala Lumpur to take part in the latest iteration of the Women’s March, a yearly protest seeking to raise awareness of gender issues in the country. This year’s iteration of the march, the first to be held in person since pandemic restrictions were progressively lifted across Malaysia starting in May of last year, focused on equal pay and an end to child marriage.

For several protesters, attending the march had unintended legal consequences, as over a dozen attendees were later questioned by local authorities for their involvement in the rally, specifically for waving rainbow flags. These police investigations represent yet another chapter in the long saga of official crackdowns on LGBTQ activism and queer-centered events in Malaysia.

The backlash against the presence of LGBTQ activists at the march further escalated when Wan Razali Wan Nor, a Member of Parliament (MP) for the opposition Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition, condemned the rally for being a pro-LGBTQ event during a parliamentary session held two days later. Wan Razali was subsequently reprimanded by parliamentary speaker Johori Abdul after admitting he was unsure whether the event was, in fact, openly advertised as a queer event.

“Feminist groups, including the Women’s March, have always been safe spaces for queer people in Malaysia,” said Gavin Chow, president of People Like Us Hang Out (PLUHO), a local grassroots organization providing health and community services to LGBTQ Malaysians. Chow, who attended this year’s Women’s March, describes the rally as a “space for women’s rights that has always welcomed queer people,” owing to the overlap between feminist and queer activism.

Chow compared the crackdown on this year’s march with similar government responses during the 2019 iteration of the event, the last one to be held in person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Many people were also investigated by the police back then for waving rainbow flags,” he said. “This was a learning experience, we developed a strategy to deal with backlash and prepare protesters for potential legal repercussions.”

Dhia Rezki, a queer activist involved in the organizing of this year’s march, highlighted a similar degree of anticipation ahead of the rally: “Any event that we organize, we have to take into consideration potential backlash or police crackdown. In this case, we provided legal information on what to do if protesters were contacted by the police, and we had queer lawyers involved in the organizing too.”

Despite the extensive legal preparation on behalf of the organizers, activists note that the scope and intensity of backlash against the rally has grown over the years. Thilaga Sulatireh of Justice For Sisters, a grassroots organization that monitors and reports on violence and persecution against Malaysian sexual and gender minorities, noted the growing polarization of right-wing counter-protesters: “Back in the early days of the march, backlash was essentially online. Over the years, however, we’ve seen an increase in the physical harassment of protesters from non-state actors, peaking during the 2019 edition.”

The emboldening of Malaysia’s far-right has become a growing concern for many activists on the ground, with many linking it to the radicalization of conservative politics in the country, which has hit the Malay and Muslim communities the hardest. During Ramadan in 2022, the Penang deputy minister imposed a fine of RM1,000 ($226) and jail time of up to a year for Muslims caught not fasting. Similarly, for Ramadan this year, several McDonald’s restaurants across Malaysia announced they would not be serving Muslim customers during daytime.

Dhia, who became a full-time activist through his involvement with JEJAKA, a space for Malay and Muslim gay men in Malaysia, ties the growing intertwining of religion and politics to anti-LGBTQ stances adopted by politicians. “There is a common strategy of scapegoating queer people for Malaysia’s problems,” he said, highlighting how queer identity is framed as being antithetical to Islam.

He situated the role of JEJAKA in this context, bridging a difficult gap between being simultaneously gay and Muslim. For this year’s Ramadan, the group organized several iftar gatherings for queer-identifying Muslim men. “Reconciling religion and queerness is a very difficult and personal journey, but it is one of the core pillars of JEJAKA,” Dhia said. “We try to provide a sense of community, something that is at the core of Islam.”

While the existence of such spaces provides much needed comfort and relief for Malaysia’s queer Muslims, safety doesn’t always come as a guarantee. Last October, a Halloween-themed drag event hosted by the queer collective Shagrilla at RexKL in the country’s capital, ended abruptly after the JAWI, the federal territory Islamic religious authority, raided the venue. At least a dozen male attendees were subsequently arrested for cross-dressing.

“They told us to line up, men on the right, women on the left,” a partygoer, who chose to go by the nickname Amir, told The Diplomat. JAWI authorities are mainly tasked with enforcing Sharia law, and as such, their mandate only applies to Malaysian Muslims. “They allowed women to leave first, then [non-Muslim] men. They charged several Muslim men with cross-dressing, even though some of them were only wearing earrings, or an obvious Halloween costume.”

The crackdown is reflective of a broader policy push focused on reinforcing the gender binary, as highlighted by the government’s ban on children’s books discussing sexual and gender identity in February, as well as the introduction of restrictive dress codes for foreign performers in March.

For long-term activists like Chow, however, the raid is hardly surprising. “A lot of the outrage came from younger queer folks who aren’t used to this kind of violence, although this has been happening for a long time,” he said. Nonetheless, Chow praised the youths’ effort in taking to social media, namely Twitter and Instagram, to denounce the raid and raise awareness of the issue.

Sulatireh also highlighted the increased involvement sought by attendees in the aftermath of the raid, saying that “many of them didn’t know their rights or due process” at the time, and that the community came together to “create a support system, even from non-activist LGBTQ people.”

On the other hand, political responses fell short of uplifting the debate. Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim later reiterated that Malaysia would not recognize LGBTQ people, adding to the already complicated relationship between the country’s queer community and their newly-elected PM, who was wrongly accused of sodomy by members of the ruling United Malays National Organization (UMNO), Anwar’s former party, in 1998.

Originally sentenced to a nine-year prison term, Anwar was released in 2004 after the verdict was overturned. While in prison, he became the leading figure of the Reformasi movement against UMNO’s dominance of Malaysian politics. Although the accusations are now widely considered to have been forged to silence him as a political opponent to long-lasting rival Mahathir Mohamad, critics of Anwar have continued to use them to connect him to Malaysia’s LGBTQ community.

“LGBTQ-phobia was at the heart of the 2022 general election, with edited clips and videos trying to link Anwar to the LGBTQ+ community,” Sulatireh explained. Chow added that the opposition made “attempts to discredit the PH coalition and leverage political influence by claiming that PH isn’t Muslim enough to represent Malaysia.”

Despite Anwar’s silence on the police investigations launched into the Women’s March, Chow says that there’s an opportunity for local activists to respond and engage MPs on the question of LGBTQ repression. “If we don’t respond, public discourse will shift toward their narratives, so we have to learn to express our voices in Parliament at a time like this,” he said. Dhia echoed this sentiment, emphasizing the importance of engaging both in person and online, as “monitoring how public sentiment shifts can later trigger necessary parliamentary discussions.”

Securing political support from elected officials is a necessary strategy to achieve concrete policy implementation, as was the case to make pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), an HIV preventive medicine, free in government clinics across Malaysia. The campaign, spearheaded by the Malaysian AIDS Council, has received support and contributions from local queer and sexual health advocacy groups, as well as significant backlash from conservative and religious groups.

“The pilot project was shunned out of fear that making PrEP more accessible would normalize LGBTQ+ attitudes,” recalled Sulathireh. “Many conservative groups came forward saying taxpayer money should not be used to fund this deviance. This isn’t just about queer people’s right to live anymore, it’s also about our right to health.”

Amid the backlash, however, Dhia highlights the key role played by political figures to support the initiative. “The Ministry of Health has always been behind us,” he said. “They understand HIV/AIDS is a public health issue, not a social issue, and they’re not backing down on making PrEP available for free across all government clinics.”

Despite the growing polarization and radicalization of the domestic political climate, Chow expressed hopes that increased linkages between civil society groups and political parties, as well as growing exposure in both traditional and social media, can help build institutional knowledge that can be passed to future generations of activists.

“Changes in government, the end of UMNO dominance on politics, and seeing Najib Razak in jail made Malaysians feel that they finally play a role in the democratic process,” he said. “The rise of social media and more conversations on political rights and transparency, young people are more willing to channel their anger into activism, and that’s definitely a positive outcome.”