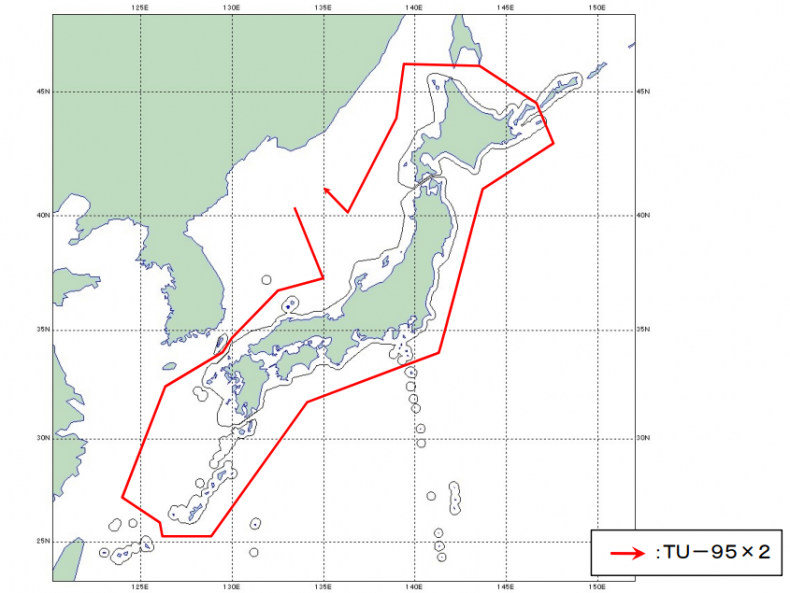

On Tuesday, January 26, Japan’s Ministry of Defense revealed that the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force had scrambled jets in response to two Russian Tu-95MS “Bear” strategic bombers near its air space. According to a map released by the Japanese government, the two Russian bombers approached Japanese airspace from Russia’s Primorsky province, flying over the Sea of Japan, and eventually flew along the perimeter of Japan’s territorial airspace, encompassing the four main Japanese islands of Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and Hokkaido, before returning to Russia.

The incident isn’t the first incident involving Russian strategic bombers near Japanese airspace by any means. Moscow regularly conducts such activities and Japan scrambles fighters to ensure that its territorial airspace isn’t violated.

However, the Tu-95’s flight path in this instance—along the perimeter of Japan’s islands—appears more provocative than usual. Generally, Russian bombers fly long-distance runs. For instance, Russian Tu-95s have been known to fly the length of the Ryukyu Island chain before returning to Russian airspace. (I discussed one such incident here at The Diplomat in late 2013.) Last March, Japan intercepted and escorted a Tu-95 over the Korean Strait between South Korea and Kyushu.

In 2014, shortly following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and ensuing isolation from the West, including expulsion from the G8 within which Japan is a member, Russian Tu-95 bomber patrols picked up in intensity in the Asia-Pacific region. As General Herbert “Hawk” Carlisle, the commander of the U.S. Pacific Air Force, said at the time, the United States noticed that Russian bombers were coming out to airspace near California and, similar to Tuesday’s incident, circumnavigated Guam. Even though Russia claims these exercises are routine patrols, intended to keep its Tu-95 bombers airworthy—which, given problems with Russian military aviation, isn’t entirely an unbelievable reason—the bomber flybys have a geopolitical messaging purpose.

Consider also that in late 2015, as my colleague Prashanth Parameswaran reported, Japanese officials publicly noted their growing concern about provocations from Moscow. Relations between Japan and Russia have declined since Moscow’s foray into Ukraine, despite Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s initial bonhomie with Russian President Vladimir Putin after coming into office in late 2012.

The territorial dispute between Russia and Japan over the sovereignty of the Kuril Islands—a lingering problem since the end of the Second World War—appeared to initially be heading toward resolution, but stalled last year. In fact, Russia moved to directly provoke Japan by announcing its intention to construct military and civilian infrastructure on the Kurils. In 2014—again, following its invasion of Crimea and G8 expulsion—Russia staged military drills on the Kuril Islands. The two countries ended 2015 with an indefinite postponement of a Putin state visit to Japan over the issue of the Kuril Islands.

In the context of the overall state of Japan-Russia bilateral relations, Tuesday’s circumnavigation of Japan’s main islands can be seen as one more provocation in a string of several over the past years. Incidentally, the incident comes just days after Abe, in an interview with Japan’s Nikkei, said that he wanted to engage Russia again. Abe currently chairs the G7 and said he wanted “constructive engagement of Russia.” Japan’s foreign relations remain complicated in its neighborhood and Abe is less-than-enthusiastic about the prospect of Japan bearing out the consequences of the West’s decision to isolate Russia.

Interestingly, as Samuel Ramani recently noted in The Diplomat, Russia’s harsh response to North Korea’s recent nuclear test could presage some positive engagement between Moscow and Tokyo—both Japan and Russia had a place at the table in the long-stalled Six-Party Talks. Since its isolation from the West, Russia had chosen to engage North Korea, going as far as to invite Kim Jong-un to its commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Second World War (an invitation Kim declined). In November 2015, a Russian military delegation visited Pyongyang as well.

Given Russia’s response to North Korea and Abe’s recent overture to Moscow, a warming of relations between the two countries may have been in the offing. However, given Russia’s decision to stage a highly provocative circumnavigation of Japan by nuclear bombers, it’s more likely than not that the cool bilateral climate that persisted through 2015 is here to stay.