A year ago, on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Since it burst into the headlines in Wuhan, China, the virus has infected over 118 million people worldwide, killing 2.6 million. Beyond that, however, the associated lockdowns have devastated economies and shaken up established political orders – or solidified them in countries that have fared relatively well. Numerous analysts have identified the pandemic as a turning point in world history, with ramifications for everything from climate change to the global balance of power.

How has the world’s worst pandemic in a century changed the Asia-Pacific region? Below, we summarize the shifts underway in East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Central Asia.

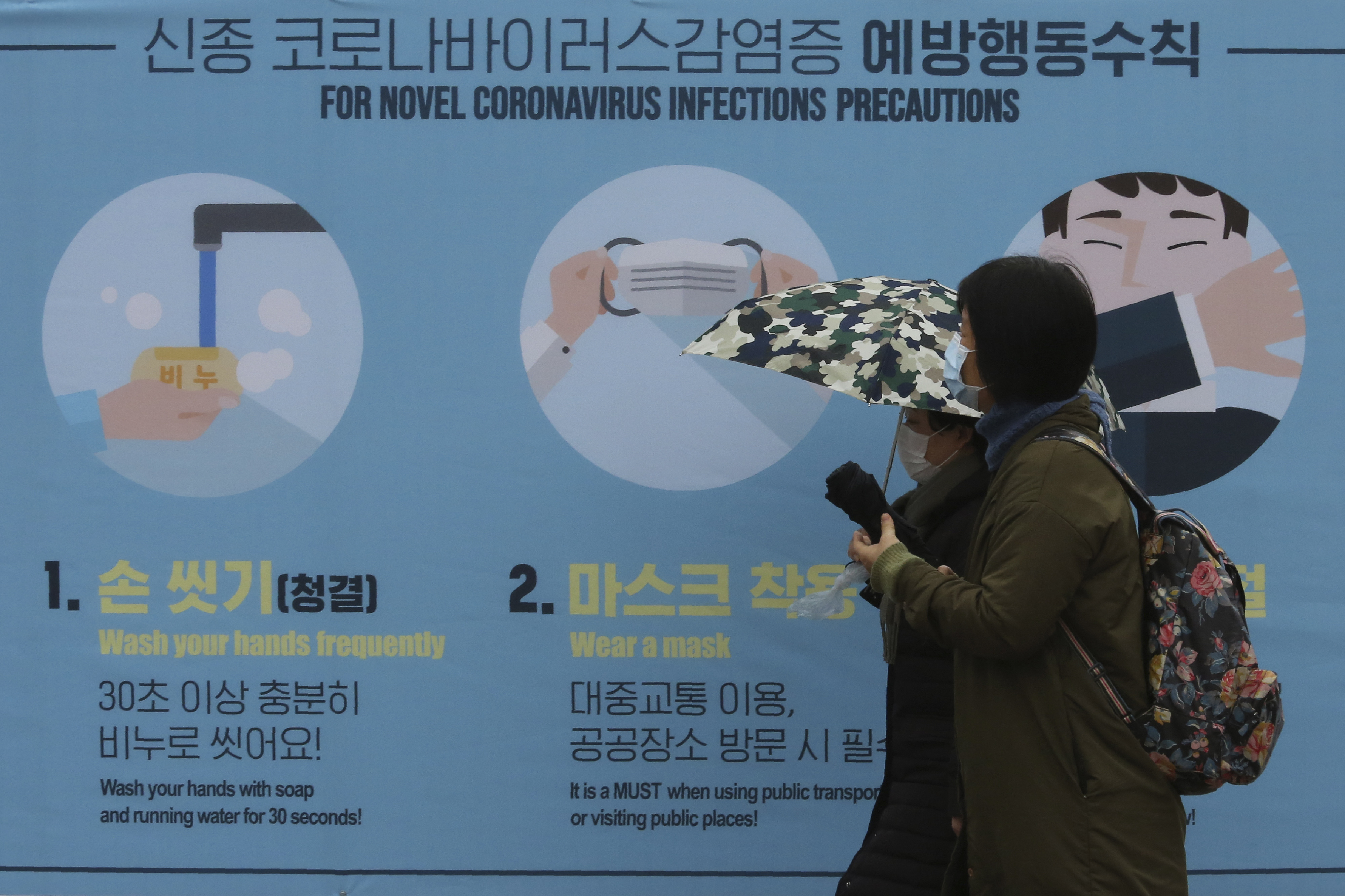

People pass by a poster about precautions against the illness COVID-19 on a street in Seoul, South Korea, Wednesday, Feb. 12, 2020. AP photo by Ahn Young-joon.

East Asia

–Shannon Tiezzi

Over a year since COVID-19 burst onto the scene, the East Asian region has weathered the storm remarkably well. The hard data of case counts and deaths puts the region among the world’s top performers: Japan has the most cases in the region at 443,000 as of March 11, with Taiwan boasting the fewest, at just 978. China, where COVID-19 was first detected, escaped with under 100,000 cases in total, if we take the official count as face value (and even if we don’t, it seems clear that the scale of deaths and hospitalizations was under control by the early spring of 2020, when things were just ramping up in other countries).

But even in East Asia, where the direct damage in terms of infections, deaths, and hospitalizations has been limited, COVID-19 has left a definite mark in other ways.

Politically, COVID-19 has toppled some leaders. The pandemic may have helped bring an end to the political career of Abe Shinzo, Japan’s longest-serving prime minster. He stepped down in September 2020 due to health concerns, but speculation is rife that public criticism over his government’s COVID-19 response played a role as well. In Mongolia, protests overs the government’s pandemic management led to the shock resignation of Prime Minister Khurelsukh Ukhnaa in January 2021, leading to the rise of a leader from a new generation.

Meanwhile, South Korea’s leaders enjoyed a political boost thanks to the government’s relatively successful handling of the pandemic. President Moon Jae-in’s Democratic Party was able to lock in a supermajority the April 2020 legislative elections, in part because of its deft COVID-19 response.

Taiwan in particular has been making the most of its moment in the sun, as its government receives rare attention on the world stage for something other than cross-strait relations. Taipei’s successful handling of the pandemic led to increased focus on its exclusion from the World Health Organization, and a highly publicized (albeit unsuccessful) campaign to restore its observer status.

More recently, however, delayed vaccine campaigns in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have brought more negative attention to their governments as other developed countries surge ahead.

China is a special case. While its government eventually pivoted to a strict policy of localized lockdowns, mass testing, and technology tracking to contain the spread of the disease, the initial botched handling has not been forgotten. As just one example, Chinese netizens continue to post mournful messages on the Weibo page of Dr. Li Wenliang, who attempted to warn his colleagues about the new virus, only to be summoned for questioning by the police. His death from COVID-19 in February 2020 sparked a national wave of grief and anger, highlighted by the brief blooming of the hashtag #IWantFreeSpeech. It’s easy to forget this anger amid the pride engendered by China’s eventual success. But Chinese citizens – particularly the residents of Wuhan, the pandemic’s first epicenter – lived with the direct reality of the confusion caused by government lies and obfuscation in the early days of 2020, and they remember.

Economically, the pandemic has had even more of an impact. China has boasted about being the only major world economy to post growth in 2020, but the paltry 2.3 percent rise in GDP is a major blow, even if things could have been much, much worse. Taiwan did slightly better, with just below 3 percent GDP growth, while Japan, Mongolia, and South Korea all registered contractions (4.8 percent, 5.3 percent, and 1 percent respectively).

North Korea, which slammed its borders shut in early 2020 and still has not reopened them, may have suffered the most of any economy in the region, although hard data is hard to come by. The devastation was enough to spark a rare tearful apology for economic failure from leader Kim Jong Un, but he has responded by doubling down on government control and military programs.

Finally, the COVID-19 crisis plunged U.S.-China relations to a historic low not seen since they established diplomatic ties in 1979. The pandemic essentially unleashed the most hawkish members of the former Trump administration, spearheaded by then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, to freely criticize China, from conspiracy theories alleging the virus was created in a Chinese lab to strident complaints about long-standing concerns like human rights and IP theft. And the United States is not alone: from Europe to Southeast Asia, public views of China have noticeably soured over the past year. Whether that’s due directly to the pandemic or to China’s highly publicized actions to quell dissent in Hong Kong and Xinjiang is harder to say, however.

The rise in U.S.-China tensions in particular has impacted the diplomatic contours of the entire region. While China’s leaders officially leave the door open for a return to the “right path” of U.S.-China relations, they are adamant that Beijing will not budge on its “core issues” – and are preparing, in their own way, for decoupling. And the downturn in U.S.-China relations has led to a corresponding freeze in cross-strait relations, as China takes aim at Taiwan. Meanwhile, in early 2020, South Korea and Japan were both on the cusp of a major step forward in relations with China (in the form of planned visits to each country by Xi Jinping). Now, Seoul and Tokyo join the ranks of regional countries increasingly nervous about what it might mean to be forced to choose between their top security and economic partners.

A medical team member checks a passenger’s body temperature at a Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) station in Jakarta, Indonesia, Friday, March 6, 2020. AP photo by Tatan Syuflana.

Southeast Asia

–Sebastian Strangio

Compared to many other parts of the world, the nations of Southeast Asia have weathered the pandemic year with remarkable, and somewhat unexpected, success. Only four of the region’s 11 nations – Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Myanmar – had recorded more than 100,000 cases of COVID-19 cases as of March 11, the anniversary of the pandemic, and only five sat in the top 100 nations for total COVID-19 cases.

Even the Philippines and Indonesia, which have seen the region’s most serious outbreaks, sit outside the circles of the world’s worst affected nations. Indonesia has recorded the 18th most cases globally, and the Philippines currently sits in 30th place, yet neither is in the top 100 for total infections per capita. At the same time, Cambodia, Laos, Brunei, and Timor-Leste have recorded caseloads numbering merely in the hundreds, while Vietnam’s success in swiftly containing COVID-19 has seen it accrue global plaudits and invaluable “soft power” reserves.

The reason for Southeast Asian nations’ relatively strong showing, given the ramshackle health infrastructure in many parts of the region, remains something of a mystery. A number of theories have been adduced, from the region’s tropical climate to the prevalence of social norms (mask wearing, the lack of handshaking, etc.) that have stemmed the spread of the disease. It is possible that an as-yet-unknown scientific factor has aided some of Southeast Asian nations; preparation and timely lockdowns have also no doubt played a role, as has simple luck.

Yet COVID-19 has nonetheless shaped Southeast Asia in important ways over the past year. The pandemic has triggered the most severe economic recession since the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. Every economy in the region bar that of Vietnam contracted during the pandemic year, led by a whopping 9.5 percent drop in the Philippines and 6.1 percent in tourism-dependent Thailand. Indeed, in many countries, the economic downturn of the pandemic may end up eclipsing the public health cost.

The statistics fail to communicate the personal hardship that has resulted from COVID-19. In September, the World Bank predicted that the number of poor people in Asia is set to rise for the first time in 20 years, and that a combination of “sickness, food insecurity, job losses, and school closures could lead to the erosion of human capital and earning losses that last a lifetime.” As in nearly every country, this has fallen most heavily on marginalized groups, including women, migrant workers, and those eking out a living in the informal sectors of the region’s economies.

Although Southeast Asia’s economies are expected to return to positive growth this year, the scale and speed of the recovery is highly dependent on the efficacy of governments’ vaccination campaigns. All 11 nations have now begun distributing vaccines. Most have begun with frontline health workers and the elderly, while heads of government have received early doses, often on live television, in order to encourage the public to embrace the new vaccines. But vaccine rollouts are already facing hurdles, from the challenge of procuring enough doses to the difficulties posed by logistics and cost of distributing them into the most remote corners of the region.

Recently announced plans for a possible ASEAN vaccine certificate will be an important step in the region’s recovery, but until widespread vaccine coverage is reached, present gains will remain fragile and subject to sudden reversals. Myanmar saw spikes late in 2020, after months of low case numbers, which now threaten to spiral out of control in the midst of the country’s deteriorating political crisis. Meanwhile, Cambodia is currently battling its first serious outbreak of the disease.

Even once vaccination is complete, it is likely that the pandemic has set in motion political and economic forces that will likely continue to echo through the coming decade.

One result has been to accelerate Vietnam’s rise and increase its regional strategic prominence. It is now the fourth-largest economy in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the pandemic year saw it eclipse the Philippines in terms of per capita GDP, with Indonesia now within its sights. This has emboldened Vietnam’s communist leadership to take a more active role on the regional and global stage.

COVID-19 also underscored the brute fact of Southeast Asia’s geographic proximity to and economic entwinement with a rising China, whose own economic recovery will be important in the region’s attempt to pull itself from the pandemic slump. The likely result will be a growing tension between Southeast Asian nations’ concern about Beijing’s growing power and belligerence, and the desire to benefit from economic partnership with their giant regional neighbor.

The domestic effects in many countries will be profound, yet hard to predict in their specifics. Economically, the disease has increased concentrations of income and economic power. Politically, it has helped accelerate the reactionary wave of the past decade, giving autocratic leaders from the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte to Cambodia’s Hun Sen a pretext to equip themselves with sweeping new powers, and impose curbs on political opponents. This trend has been opposed by the emergence of an incipient regional anti-authoritarian protest movement, setting the stage for political crises in many Southeast Asian countries.

In 1997, the Asian financial crisis touched off a range of political crises in Southeast Asia: it brought down the New Order of Suharto in Indonesia, spawned the reformasi movement in Malaysia, and catalyzed the rise of Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand. By heightening pre-existing conflicts and tensions, COVID-19 has set the stage for a decade of tumult.

Community health workers screen a man for COVID-19 symptoms in Dharavi, one of Asia’s biggest slums, in Mumbai, India, Saturday, Aug. 15, 2020. AP Photo by Rafiq Maqbool.

South Asia

–Abhijnan Rej

A year since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic, it is hard to escape the conclusion that, in a manner of speaking, South Asia has managed to beat the odds when it came to dealing with the immediate first-order effects of the disease – especially against the dire prognoses that were made about the region around this time last year. Concurrently, the pandemic has opened new geopolitical opportunities for countries like India. It has also enabled consolidation of ruling forces’ grip on power across the region, through measures fair and foul.

Let us start with raw numbers to see how South Asia has done thus far in containing the pandemic in the form of a single metric: the number of deaths from COVID-19 per million people. As of March 11, statistics provider Statista reports Sri Lanka’s tally stands at 23.44, Bangladesh’s at 52.11, Pakistan’s at 61.77, Nepal’s 105.28 and India’s 115.77. Computing Afghanistan’s COVID-19 deaths per million using Johns Hopkins fatalities numbers puts it at 64.5. The Maldives has reported 64 deaths from the novel coronavirus to date, and the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan just one so far (in January this year).

Comparing these numbers to those from key advanced Western economies – the United Kingdom’s deaths per million figure stands at 1,863.74, the United States’ 1,600.88, France’s 1,314.75 and Switzerland’s 1,175.77 – one is left with a puzzle best left to medical and public health specialists: that despite stressed and underdeveloped medical infrastructure, rampant poverty, and middling state capacity, South Asia has emerged from the pandemic bruised, but not broken.

To be sure, such comparisons cannot be taken too literally. There is certainly a degree of underreporting of cases and fatalities in South Asian countries at play here. That said, at least in India (the worst performer using the metric above), the reported numbers track well with experience, anecdotally speaking of course. Few families I know have lost loved ones to the disease; public spaces are now mostly open; and the unmistakable feeling that the worst is over, and the country is poised for a rebound, is in the air.

Emerging relatively well off in terms of the immediate public-health effects of the pandemic has also opened significant geopolitical space for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The pandemic, ironically enough, has afforded the moribund South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation an opportunity for revival, hobbled as it had been with the perennial India-Pakistan rivalry. Modi has also deftly deployed vaccine diplomacy as a tool to mend ties with India’s neighbors, including through a commitment to supply 9 million doses of an indigenously manufactured vaccine to Bangladesh. India’s vaccine manufacturing capacity has also seen it emerge as a leading contributor to the WHO-led COVAX program, with the country committed to producing 1.1 billion doses for global distribution in total. Already through COVAX, Indian vaccines have been shipped as far as Africa, while bilateral (commercial) arrangements have been made for India to supply vaccines to Brazil. Interestingly, an India-made vaccine will also make it to Pakistan through the COVAX distribution system.

Domestically, the pandemic has afforded Modi a signal opportunity (along with the military standoff with China in eastern Ladakh) to reshape India’s economic trajectory under the garb of “self-reliance” – a notion in line with deeply held nationalist beliefs of both the right as well as the left. But what has been equally interesting is that Modi’s decision to impose a harsh nationwide lockdown, which led to the largest internal mass migration in India’s history last summer, did not seem to carry any political costs for him in regional elections, including in Bihar (which the New York Times described as a “referendum” on the government’s COVID-19 response).

In neighboring Pakistan, the military took charge of the COVID-19 response, strengthening its already iron grip over the country and bolstering its image – even as opposition Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz leaders took aim at the hallowed institution during protests last year. Summarizing the political effects of the pandemic in Pakistan, Brookings scholar Madiha Afzal wrote in August last year, “the pandemic’s aftershocks have weakened the country’s current civilian government, further emboldened its military, and brought about a broader crackdown on dissent.”

In Bangladesh, COVID-19 restrictions provided the ruling Awami League government an opening to intensify its crackdown of dissenting voices; Nepal has also seen the ruling K.P. Sharma Oli-led government (whose future is anybody’s guess now, amid deep political turmoil) use the pandemic to go after voices that it deems inimical, including journalists. The pandemic has also exposed the majoritarian impulses of certain South Asian governments, with Sri Lanka’s Rajapaksa brothers banning the burial of Muslims in the island state for months on ostensible public-health grounds – a ban that was only recently lifted following months of protests and international pressure.

A medical specialist, wearing a protective suit, checks a young woman’s, lung X-ray inside a restaurant that was converted into a clinic in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, Wednesday, July 22, 2020. AP photo by Vladimir Voronin.

Central Asia

–Catherine Putz

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose — The more it changes, the more it’s the same thing. To say that COVID-19 changed Central Asia would be a stretch. What changes we can observe are on the surface, mere tinkering with rhetoric, or at the deepest extent, the acceleration or deepening of processes already in progress.

Like much of the world, when the coronavirus was first detected in Central Asia – in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan in mid-March – the first response was to shut down. Borders were closed, flights halted, and people ordered to stay home under states of emergency.

The Kazakh government went a step further, pursuing “fake news” charges against an activist criticizing the government’s pandemic response; the Uzbek government amended its criminal code in late March to criminalize the distribution of “false information” and the Tajik government approved amendments criminalizing the same in the summer of 2020. The Kyrgyz parliament passed its own “fake news” law in the summer of 2020, too, but then-President Sooronbay Jeenbekov rejected it in August. Arguably these legal changes were already coming – mirroring laws passed in Russia in 2019 – but the pandemic provided a handy excuse and immediate use cases.

The economic realities of the region motivated re-openings by the summer of 2020, but World Bank analysis indicates that the region experienced a contraction during the pandemic year. Broken out by country, however, it’s clear other dynamics were also in play: Kyrgyzstan’s estimated 8 percent contraction in 2020, which dragged the region’s stats down, arguably has roots in COVID-19 but deeper links to its political turmoil. The wider pandemic situation continues to hammer regional economies, but in predictable ways. For example, Tajik migrant workers are always among those who suffer when the Russian economy wobbles. COVID-19 has shaken the Russian economy, for sure, and with the addition of continued travel restrictions making it difficult for labor migrants to move about the region Central Asia’s migrant workers still face employment woes.

The pandemic hasn’t necessarily made the countries of Central Asia more autocratic, nor has it changed the realities of the region’s economies. So what has changed?

To those in Central Asia who have had loved ones pass away, the above analysis may appear heartless. Plenty has changed for those whose grandfathers and grandmothers have died, or mothers or aunts or friends – especially those in countries like Turkmenistan, which continues to deny the existence of the virus within its borders, or Tajikistan, which delayed admitting the virus and now claims to be COVID-free. But that, also, is par for the course: lack of transparency, gaslighting whole populations, and the disregard by governments of the pain and suffering of individuals.

Recent analysis of global mortality rates, by Ariel Karlinsky at Hebrew University in Israel and Dmitry Kobak at the University of Tübingen in Germany, highlighted in a Eurasianet article last month suggests that the human cost of the pandemic in Central Asia is much greater than state statistics demonstrate. In Karlinsky and Kobak’s preprint paper (meaning it has not yet been peer-reviewed), the researchers compared the ratio of excess mortality during the pandemic with officially reported COVID-19 death counts and identified the highest undercount in Uzbekistan, with Kazakhstan also displaying a high undercount. “Such large undercount ratios strongly suggest purposeful misdiagnosing or underreporting of COVID-19 deaths,” the authors wrote. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan were among the countries with the highest relative increases in deaths per 100,000 people, too. With time and more data (and, critically, more accurate data) the true human cost of the pandemic in Central Asia may become more clear.

The lasting impact, however, is hard to chart at this juncture. As vaccines enter the region, regional propaganda – either that the pandemic has been well-controlled by regional governments, has passed (as Tajikistan claims), or never arrived, as in Turkmenistan – may undermine efforts to cajole populations into volunteering for a vaccine.